A study of Contemporary Buddhist-Muslim Relations in Sri Lanka Part 3

Posted on September 27th, 2017

by Prof. G. H. Peiris

August 27, 2017

Continued from Part 2

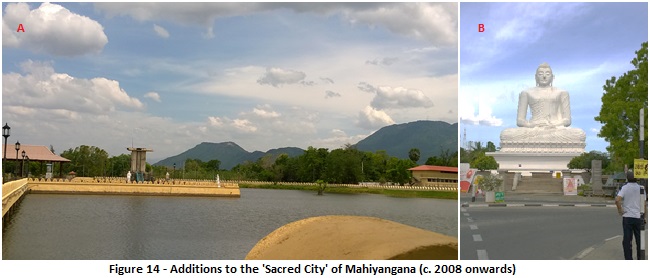

As a further advancement of the project an extent of about 60 hectares (150 acres) around the Rajamaha Vihāraya was demarcated to occupy almost the entire southern segment of the town as a ‘sacred city’ (Figure 13). Within it several new religious monuments such as the ‘Dutugæmunu Pilgrims Rest’ and a statue of the monarch (Figure 12C), a ‘Relic Chamber’, a protective wall and gold-plated fence round the sacred bō-tree (sapling of Sri Maha Bodhi), a Makara Thorana and an ornate pathway leading to the stūpa (Figure 12D), and a residential complex for monks were built, some of it with devotee donations and all in the three-year Premadasa regime. Secular tertiary functions (other than the wayside sale of artefacts by vendors from the Vedda community in Dambāna) thus came to be confined to the northern segment of Mahiyangana, designated the ‘New Town’ as a separate administrative unit (grāma niladhāri area). Not to be outdone, Mahinda Rajapaksa, early in his first term of office as president (2005-10), initiated work on a massive Samādhi statue of the Buddha at the centre of the New Town (Figure 14B), a large ‘sermon hall’, and added to these meritorious acts the conversion of a pond in the ‘sacred city’ to an artificial lake covering an extent of about 7 hectares with a part of it bordered by a parapet of the well-known ‘valākul bæmma‘ of Kandyan temple design (Figure 14A). In addition, a shrine of great antiquity associate with occult powers (anuhas) at Rideemāliyædde a few miles southeast of Mahiyangana was renovated and made ready “for the serene joy and emotion of the pious”.[i] The latest act of political piety is President Maitripala Siridena’s sponsorship to the installation of a solar electricity supply system to the shrines in the sacred city.

The ‘sacred area’ of Mahiyangana is, indeed, a surprising vista to those (like me) exploring it after a gap of several decades. While Buddhist icons and other symbols are ubiquitous in almost all parts of Mahiyangana, within its ‘sacred city’ there has been an almost total transformation of the earlier atmosphere of disrepair and disarray, due mainly to the fact that some of the former presidents have left their imprint in the form of shrines and diverse embellishments, thus creating an ambiance of sanctity and order befitting one of the most venerated temples in Sri Lanka.

In the entire town it is also possible to observe another unusual feature in comparison to other urban centres of similar size in the predominantly Sinhalese areas of the country ̶ namely, the absence of any non-Buddhist place of worship (no church, kōvil or mosque) discounting the ‘mosque’ closed down after the attack on 11 July 2013.

Over several months prior to the Prayer Room attack there had been attempts by the BBS to promote in Mahiyangana a rift between the Buddhist and Muslim segments of its population. This could well have been aimed primarily at weakening the popular support which President Rajapaksa enjoyed in this area, as evidenced by his obtaining in 2010 60.1% of the popular vote to his opponent’s 37.7%. Past electoral records show, however, of Mahiyangana being an electorate where there have been extraordinarily large shifts of support between the two main contestants ̶ UNP- and SLFP- led coalitions ̶ comparable in magnitude to those witnessed in Mawanella. This is probably why Mahiyangana became one of the early venues of the Ven. Gnanasara campaign of destabilisation.

Yet, it was here that he encountered, probably for the first time, a fairly formidable opponent in the person of Ven. Wataræka Vijitha, the Chief Incumbent of a small temple named the ‘Rothalawala Mahaveli Mahavihāraya’ (located 24 km north of Mahiyangana, but within the same parliamentary electorate and Pradēsheeya Sabha/PS area). Vijitha Thero was a member of the PS, elected as a candidate of the party headed by Rajapaksa, and an ardent advocate of inter-religious harmony ̶ especially Buddhist-Muslim relations. Following the attack on the Mahiyangana Muslim ‘Prayer Room’ (sketched out below) it was Ven. Vijitha who disclosed in the course of an address to the ‘Up-Country Muslim Council’ (Figure 15 A) that there was a discussion of BBS operatives led by Ven. Gnānasāra at the premises of the Rajamaha Viharaya on the day before the attack.

This resulted in what should be described as a sustained series of rabid attacks on Ven. Vijitha by the BBS, in certain incidents, personally led by Ven. Gnānasāra. There was, first, a demonstration of protest at the Rothalawala temple by a group claiming to be members of its Dāyaka Sabhā (‘devotees society’), instigated by unseen hands, demanding the eviction of Vijitha Thero from the temple on grounds of immoral conduct and inordinate links with the Muslim community. The police intervened to ensure the monk’s physical safety. This was followed by a more criminalised threat (Figure 15 B & C). In early April 2013 a large crowd assembled at the premises of the Mahiyangana PS office declaring that Ven. Vijitha has no right to participate as a representative of the people in an on-going meeting of the PS. A part of the crowd became so aggressive that a formidable police contingent that had arrived in the scene had to rescue to Thero and remove him to participate as a representative of the people in an on-going meeting of the PS. A part of the crowd became so aggressive that a formidable police contingent that had arrived in the scene had to rescue to Thero and remove him to safety (Figure 15 D).

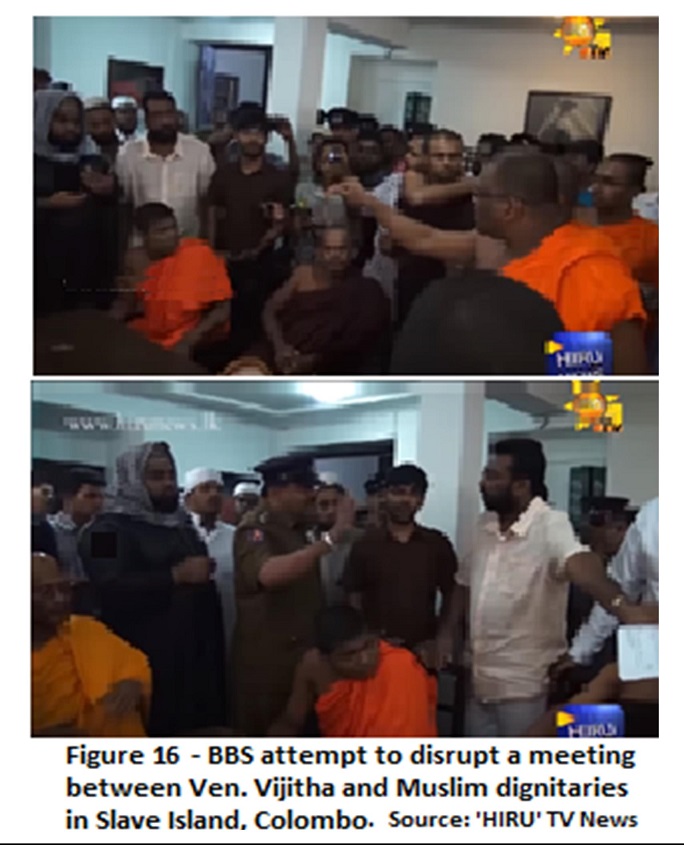

The follow-up of this incident is of relevance to an understanding of the political dimensions of the Mahiyangana turbulences. The scene of persecution of Vijitha Thero shifted to Colombo. A boisterous mob led by Ven. Gnānasāra forced its way one morning into the office of the Ministry of Industry and Commerce, Rishard Bathiyutheen (according to his detractors, a ‘land grabber’ from the ‘Wilpattu Nature Reserve’ in the northwest of the island), in pursuit of Ven. Vijitha who, they claimed, was hiding in that office. The police, exercising utmost patience, persuaded the mob to depart. A similar publicity-seeking raid was repeated by Ven. Gnānasāra gate-crashing a meeting between leaders of the Muslim community in Slave Island (a locality in Colombo) and Ven. Vijitha whose ‘reconciliation’ efforts had meanwhile gained wide publicity. Video clips of the raid (Figure 16) suggest that an outbreak of violence was averted, once again, due to police intervention.

Shortly thereafter, early one morning, Ven. Vijitha was found dumped in a roadside ditch about 5 km to the interior of Panadura (a coastal town about 20 miles south of Colombo), assaulted, wounded and stripped of his robes. There are two conflicting versions of this sordid episode. One, as alleged by the victim, that BBS operatives were responsible for the crime; and the other, that the entire scenario of assault and humiliation was stage-managed by Vijitha and his wounds were self-inflicted. The police, somewhat strangely, supported the latter version. I am inclined towards the view that these despicable events were an outcome of Ven. Gnānasāra and his followers seeing in the Jāthika Bala Sēnā (‘Army of National Power’) formed by Vijitha Thero, an emerging challenge to his ‘Army of Buddhist Power’ (Bodu Bala Sēnā), that must be nipped in the bud.[ii]

The Sangha elite of Sri Lanka in general appears to have remained aloof of this BBS generated storm in Mahiyangana. But Ven. Vijitha (though not in that elite), who by this time had strengthened his Jāthika Bala Sēnā, was by no means alone in ethnic reconciliation efforts. There was, for instance, an incident in the immediate aftermath of the Pradēsheeya Sabhā offensive referred to above that involved a meeting of the Bhikku elders of the area summoned by Ven. Urulæwatte Dhammakeetti, the Chief Incumbent of the Rajamaha Vihāraya, to proclaim a prohibition of Ven. Vijitha from participating in Buddhist activities of the area on the grounds that his “improper conduct” has the impact of destabilising the Buddhist community. But, there was an immediate and a far more authoritative response to this decision by the exalted Kāraka Sangha Sabhā of the Asgiriya Chapter (which has overarching control of several Rajamaha Vihara including that of Mahiyangana) that the proclamation by Ven. Dhammakeetti was illegal and, hence, null and void.

The ‘reconciliation’ campaign with which Ven. Vijitha persisted, it should also be stressed, was part and parcel of far more formidable sponsorship and support for inter-ethnic harmony from Buddhist opinion leaders ̶ a feature which the entire range of forces bent on

destabilising Sri Lanka and rubbishing the Rajapaksa government have preferred to ignore or conceal. In order to substantiate this with just one (of many possible) illustration, I refer to the efforts by Agga Mahā Panditha Kamburugamuwē Vajira, one of the most venerated Buddhist prelates in Sri Lanka. He commenced his ethnic reconciliation efforts even before the end of the ‘Eelam War’, speaking mainly at well attended indoor meetings, sharing the platform with dignitaries of other faiths. Figure 17 provides glimpses of his participation in one such event held on 4 May 2013 (cynics should remember that this was well before the next stipulated presidential election ̶ i.e. end of 2016). Ven. Vajira delivered the main speech. Among the others who addressed this large audience were leaders of the entire spectrum of religious groups ̶ priests and lay persons, men and women ̶ were President Mahinda Rajapaksa who made one of the most passionate appeals for peace.

The story of the threat to the Mahiyangana ‘Prayer Room’ attack is best reconstructed with information obtained in the course of a dialogue I had with the son of late Sulaiman Seini Mohammed, its founder. It is worth recounting here for several fascinating insights of vital relevance to this study. Sulaiman, a migrant from Batticaloa, made Mahiyangana his home in the mid-1960s, having set up a makeshift roadside stall close to the ancient temple where his savings became adequate for him to establish a small shop close to the centre of the town in 1973, shifting from glass and plastic trinkets to jewellery in silver and gold (there is an intriguing ‘Midas Touch’ here which I did not dare to probe). As his income increased he purchased an adjoining site where he constructed a building for use as a residence. In 1991, in the course of a visit to Batticaloa, Sulaiman was abducted and severely beaten up by LTTE cadres, and dumped what his attackers thought was his corpse on the roadside, from where he was brought by his kinsmen to the Batticaloa hospital. His son does not know why the father became a victim of such an assault; but given the turbulent state of coastal towns in the east at that time ̶ mass extermination in Eravur and Kattankudi, ethnic cleansing and, in fact, the entire range of brutalities ̶ the assault was probably a torture employed by the ‘Tigers’ for extortion from successful traders. Upon receiving this news his family members rushed to Batticaloa and brought him comatose to the National Hospital in Colombo where he recovered, and returned to Mahiyangana after about three months. It was as an act of gratitude for his miraculous recovery that Sulaiman converted a section of his residence into an Islamic prayer room. Since then, until 11 July 2013, according to the son, the ‘Prayer Room’ (Figure 18) continued to serve as the venue of Friday noon rituals for a gradually increasing number of Muslims in the town.

When questioned about the nature of the mob offensive against the ‘Prayer Room’ and what happened thereafter, Sulaiman’s son (present owner of the jewellery shop) said that the attack was a sequel to a Bodu Bala Sēnā meeting in Mahiyangana held about a week earlier; that a group of about twenty drunkards arrived late that night and, in the course of their attack, manhandled and threatened his father throwing powdered chilli on his face, and defiled the prayer room with swine offal ̶ all of it, having disconnected the electricity supply and under cover of darkness ̶ quite a different scenario from the pre-noon Dambulla offensive by a large crowd. The ‘Prayer Room’ has remained closed thereafter; and its devotees have resumed their earlier practice of proceeding for Friday rituals to the mosque in the village of Pangaragammana 9 km to the south of Mahiyangana where there is a larger community of Muslims. Responding to my questions he said that there has been no decline in his trade turnover though a poster stating “We thank you for not buying from Muslims” appeared opposite his shop (as it did elsewhere in the town) during the last ‘New Year Season’ (mid-April). He also said that there is no hostility towards him from his neighbours. In the course of our conversation he referred to an altercation between two groups of youth ̶ Buddhist verses Muslim ̶ in Pangaragammana during the Vesak holidays (21-22 May) last year over an alleged burning of a Buddhist flag. It was amicably settled by the clergy from both sides, and did not affect Muslim traders in the town. Asked whether he is worried about the future his reply was: “Mmm…no, the people here like to live in peace, business is not very good, there are no rich people here.”

The manner in which an avalanche of disinformation that usually follows an offensive of this type is once again vividly illustrated by the records pertaining to the Mahiyangana attack. The fact that the controversy regarding the ‘Prayer Room’ has been amicably settled by Buddhist and Muslim community leaders at the local level has never found a place in these records. Likewise, the “live and let live” policy advocated by Ven. Wataræka Vijitha finding widespread acceptance (albeit with hardly any acknowledgement) by inhabitants of Mahiyangana has also been ignored. The post-attack propagandists focus, instead, was on conveying to the world the spectre of an intensifying enmity between the two religious groups and the alleged responsibility of the government for the deepening crisis. In the immediate aftermath of the Prayer Room attack, the fastest draw, as usual, was from the embassy of the United States which expressed “grave concern”. This was followed by a chorus of criticism and condemnation from some of the other Colombo-based diplomatic missions which, in turn, resonated worldwide. The NGO hirelings were quick to jump into the fray. At the level of the United Nations, Ban-ki Moon shed yet another crocodile tear on the plight of the Muslims, this time the Muslims in Sri Lanka. At a more damaging plane, Rauff Hakeem, the leader of the Sri Lanka Muslim Congress, said in a media statement that the Mahiyangana Mosque has been targeted for over a week in what appears to be the latest in an organized series of attacks carried out on mosques and the hate campaigns against the Muslims in Sri Lanka by extremist Buddhist groups, for many months”. According to this statement, “the son of the founder-trustee of the Mahiyangana Mosque was threatened by the Uva Province Minister on Friday morning, warning him not to conduct the Jumma prayers scheduled for that afternoon”. (Note that the “son of the founder-trustee” is probably the same person who related to me the specificities of that attack documented above). The version publicised by the SLMC leader appears to be a fabrication based on hearsay reports. Yet it was repeated in an article authored by the well-known journalist D. B. S. Jeyaraj titled ‘Mosque in Mahiyangana Closed for Prayers after Uva Provincial Minister Anura Vithanagamage of UPFA Threatens Trustee’ published in his own blog on 19 July 2013 to be copied by many others.[iii] Thereafter various excessively distorted version of the story began to appear all over the world. For instance, a journal named Arab News, which describes itself as “the leading English language daily in the Middle-East” said: “militant Buddhist monks are attacking, looting, plundering and killing Muslims as part of their well-planned strategy and are least bothered about its fallout on the country”. Finally what purports to be a scholarly synthesis into which the story of the Mahiyangana attack is infused was produced by Laksiri Fernando, a Professor of Political Science who, after having avoided political controversy while enjoying a range of career benefits under the SLFP-led governments since 1994 including that headed by Mahinda Rajapaksa, joined the band of critics of the Rajapaksas for their failure to implement constitutional reforms facilitating the devolution of power to the ‘north-east’, overlooking the obvious fact that such a reform would have the effect of unprecedented empowerment of the forces that supported the secessionist campaign led by the late lamented LTTE leadership. That is not all. With no concrete evidence whatever for his demented accusation, but ignoring all the evidence to the contrary, Fernando has declared that:[iv] “He (Gotabhaya Rajapaksa) and his brother President should take direct responsibility for the recent attacks on the religious and business establishments of particularly the Muslim community and there are all indications that these incidents happened with their full awareness if not approval“.

Grandpass Mob Violence

Eruptions of clashes between rival gangs in this part of Colombo have been somewhat more frequent than elsewhere in the country. But one needs to take into account a gamut of considerations before concluding that they represent an exemplification of intensifying religious rivalry. Several localities in this area have for long constituted the venue of the multi-ethnic ‘underworld’ of Sri Lanka and the bailiwicks of rival gangland bosses who are known to have at least slender connections with their respective political masters among whom were/are politicians at the highest level, city fathers and business magnates. This same feature has been subject to detailed observation in other South Asian cities such as Mumbai, Ahmedabad, Karachi, Delhi and Calcutta. This is why, when gangland clashes occur, there is invariably a polarisation on ethnic/religious lines (I have written about this phenomenon in my recent book, Political Conflict in South Asia, pp. 179-183, illustrating it with Karachi experiences).

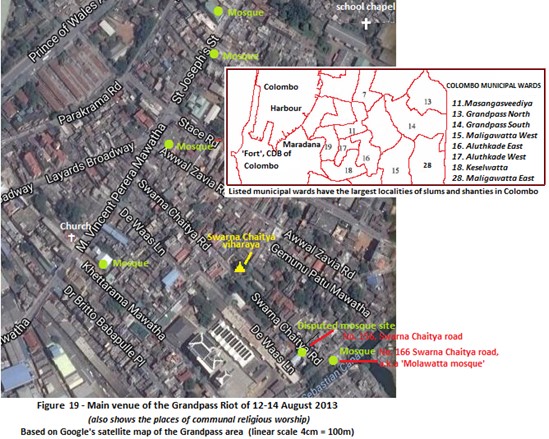

What triggered off the ‘Grandpass riot’ of August 2013 was a localised dispute pertaining to the conversion of a building (initially constructed with UDA permission for a warehouse ̶ interestingly, referred to as such by several Muslim contributors to the related documentation ̶ to serve temporarily as an Islamic prayer-room adjacent to a predominantly Buddhist residential neighbourhood into a permanent mosque. That was an outcome of an agreement between trustees of a mosque (locally called the “Molawatta palliya“) located within about 50 meters of the temporary ‘prayer room’. (Figure 19 – satellite map).

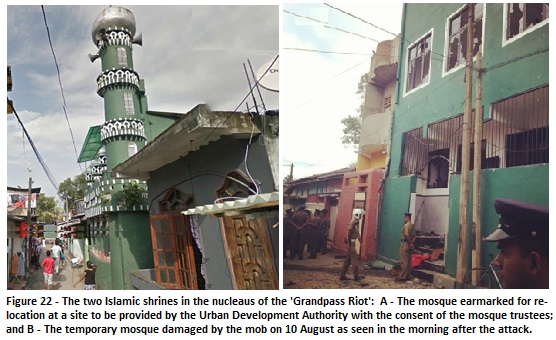

The initial disputants were the Buddhist residents of the locality including the Bhikkus of their temple, Swarna Chaitya (‘Golden Stupa’- Fig. 21), and the Imam serving as the spokesman for the Muslim devotees of the prayer-room located about one-hundred meters away along the road named after the temple ̶ in short, a dispute between two groups with different religious identities. Yet, the related details indicate in no uncertain terms that the dispute was well on the way to reaching an acceptable solution with an officially recorded undertaking by the Muslims that their prayer-room will be shifted to an alternative site at the end of the ongoing Ramadan fasting season. But then, quite unexpectedly, there was a hardening of attitudes ̶ a refusal to move, and a stance of: “We establish mosques anywhere we like, and that is our right”, on one side; and “This is a Buddhist country, our inalienable rights overshadow yours”, on the other. This turn of events, according to my interpretation of the related information, was due largely to external and extraneous interventions including those of Buddhist extremists led by an outfit named ‘Rāvanā Balaya‘ (Rāvanā Power) which appears to have been in mutual rivalry with the BBS for arrogated guardianship of Buddhist interests, and the emerging leaders of the Muslim community in Sri Lanka in competition with the older generation for political leadership of the community.

Regarding the identity of the attacked mosque (an error made in several blogs), I should clarity that the ‘Colombo Grand Mosque’ (Fig. 20), like several other architecturally grand mosques scattered throughout the city, stands in all its glory in a moderately affluent setting on New Moor Street, absolutely free of any external threat. The largest mosque in the Grandpass Ward of the Colombo municipality is ‘Muhiyaddeen Jumma Masjid’ on St. Joseph Street which, like several hundred elsewhere, has also never faced a challenge from those of other faiths. What was attacked is a far more modest and supposedly temporary structure located at No. 156 of ‘Swarna Chaitya Road’ ̶ a densely populated ‘lower middle-class’ residential neighbourhood where the Buddhists outnumber the others (Figure 19: satellite map).

There is another dimension relating to the disputed conversion of the temporary prayer room to a mosque in the type of setting described above which intellectuals who need star-class hotel settings for their sanctimonious deliberations fail to appreciate. A fully fledged mosque usually attracts large numbers of devotees on a regular basis. There has also been a relatively rapid expansion of the Muslim population in the Swarna Chaitya Road locality during the recent decades ̶ an increase from about 80 to 400 family units between 1987 and 2013.[v] There is, in addition, the electronically amplified ‘call to worship’ broadcast from minarets five times a day which, for the ‘non-faithful’, is a barely tolerable source of noise-pollution ̶ comparable practices in Buddhist temples performed once a lunar month notwithstanding. In the case of the present dispute, it is not possible to brush aside the fact that the Swarna Chaitya vihāraya (Figure 21) along with Jayanthi Vidyālaya, a well maintained school located across the road, and a social welfare centre constitute the main social nucleus for Buddhists even beyond the bounds of the Grandpass area.

The background information presented above is intended not to trivialise the outrage committed on 10 August 2013, but to indicate that these and a few other localised mob attacks on places of worship during these months did not represent a general Buddhist onslaught on the Muslims.

The narrative of a “Buddhist mob attacking a newly constructed mosque in Grandpass” on 10 August 2013 is true but not the whole truth. What does emerge from the reports available is a rather confusing story of aggressive religiosity among both Buddhists as well as Muslims in a social ethos that facilitates instant formation of mobs invariably fuelled in late evenings by booze and drugs. Earlier in 2013 a portion of the land belonging to a mosque built in the 1960s locally named the ‘Molawatta palliya‘ was earmarked for acquisition by the Urban Development Authority (UDA) for a much needed widening of St. Sebastian Canal and a ‘slum clearing’ project. The related agreement between the UDA and the trustees of the mosque involved (a) an undertaking by the UDA to offer the trustees an alternative site for re-locating the mosque and (b) the use as a temporary prayer-room a three-storey building that had been constructed close by with the stipulated UDA approval for use as a warehouse. It was the gradual refurbishing of that building for permanent use as a mosque that conveyed the impression of a surreptitious addition of a new mosque to this overcrowded residential area, while the old mosque just round the corner remained in uninterrupted use ̶ note the location of the two Muslim shrines close to the southeast margin of Figure 19 (p. 32) ̶ that made Sinhalese residents of the locality led by monks from the Swarna Chaitya temple to make peaceful representations (on 5 July) and a more formidable collective demand (17 July) that the prayer-room should be shifted elsewhere. Following an intervention by the Ministry of Religious Affairs there was an undertaking given by the mosque trustees to close down the temporary premises soon after the end of the rituals connected with the ‘Ramadan fast’ period on 7 August 2013, because meanwhile the UDA had rescinded its decision to acquire land from the old mosque premises. It was in the absence of any signs of the promised vacation that there was a build-up of tensions involving, on the one hand, the intervention of rabble-rousing Buddhist extremists from outside and, on the other, what seemed a preparation on the part of the mosque devotees to meet possible violence with violence in order to defend their right to use the new premises as a mosque.

To be continued to part 4

[i] . The complex of ancient ruins at Rideemahaliædda, especially the ancient temple in the hamlet of Uraniya (locate 17 km to the south-east of Mahiyangana) became a venue of archaeological restorations during the Premadasa presidency. The related efforts were resumed early in the presidential tenure of Mahinda Rajapaksa when, in 2007, he offered a gilded silver image of the Buddha to the temple (in acknowledgement of its mystic powers) and made a vow to defeat the LTTE, thus authenticating a folk belief that King Dutugemunu at the vanguard of his army on its way towards Rajarata more than two millennia ago to establish his rule over the entire island performed a similar ritual. The Rajapaksa, offering, like his suzerainty, has since then been stolen!

[ii]. For a far more detailed account of the persecution suffered by Ven. Vijitha allegedly in the hands of BBS operatives, see a paper titled ‘Buddhist Monk Attacked by Bodu Bala Sena and Police Inaction’

http://groundviews.org/2013/10

[iii] . As a further illustration of the ‘wildfire’ spread of false information, I refer to the Tamil Eelam Liberation Organisation (TELO) story, published on 20 July, (telo.org/?p=17442#prettyphoto), identical to the DBS Jeyaraj version, but illustrated with a photograph taken at Dambulla with the caption ‘Destroyed Mahiyangana Mosque’. This photograph is reproduced below.

[iv] . Fernando, Laksiri (2013) ‘Defence Secretary Defends Majority Domination: …’, Colombo Telegraph, July 5, 2013.

[v]. This estimate is furnished in Ranawaka, Champika (2013) ‘Grandpass – The True Story’ in Colombo Telegraph, 14 August, 2013.