Were human babies used as bait in crocodile hunts in colonial Sri Lanka?

Posted on August 10th, 2018

Anslem de Silva 1 & Ruchira Somaweera 2 Courtesy Journal of Threatened Taxa

1 Amphibian and Reptile Research Organisation of Sri Lanka, 15/1, DolosbageRoad, Gampola, Sri Lanka

2 Biologic Environmental Survey, 50B, Angove St, North Perth, WA 6006, Australia

1 kalds@sltnet.lk, 2 ruchira.somaweera@gmail.com (corresponding author)

Abstract: Use of live animals as bait is not an uncommon practice in hunting worldwide. However, some curious accounts of the use of human babies as bait to lure crocodiles in sport hunting exist on the island of Sri Lanka, where sport hunting was common during the British colonial period. Herein we compile the available records, review other records of the practice, and discuss the likelihood of the exercise actually having taken place.

Keywords: Ceylon, colonial period, Crocodylus porosus, Crocodylus palustris, live bait, sport hunting.

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.11609/JoTT.o4161.6805-9

Editor: B.C. Choudhury (Retd.), Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, India. Date of publication: 26 January 2015 (online & print)

Manuscript details: Ms # o4161 | Received 28 September 2014 | Final received 26 November 2014 | Finally accepted 03 January 2015

Citation: de Silva, A. & R. Somaweera (2015). Were human babies used as bait in crocodile hunts in colonial Sri Lanka? Journal of Threatened Taxa7(1): 6805–6809; http://dx.doi.org/10.11609/JoTT.o4161.6805-9

Copyright: © de Silva & Somaweera 2015. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. JoTT allows unrestricted use of this article in any medium, reproduction and distribution by providing adequate credit to the authors and the source of publication.

Funding: Self-funded.

Competing Interest: The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgements: We thank Franklin Hughes, Johan van Rooijen, Rohan Wijesekera, Aaron. M. Bauer, David Rhind and Henrik Bringsøe for their help in securing some literature. Charlie Manolis, John Rudge and Rohan Pethiyagoda made useful suggestions to improve the manuscript and two anonymous reviewers provided useful comments. Literature and old newspapers were accessed through the Library of Congress, Biodiversity Heritage Library and National Library of Australia.

Hunting for wild animals is stimulated by the many different human uses of faunal resources. Hunting for sport is one of the oldest recreational uses of wildlife and existed for more than 2500 years since Ancient Greek times. It was largely practiced by royalty, the upper social classes and colonial rulers (Coningham 1995; Smalley 2005; Griffin 2007). Among the many large animals hunted for sport were crocodilians. Accounts of the hunting of crocodiles are common in the 19th and early 20th century literature, and such hunting was particularly common in the British colonies (MacKenzie 1997; Taylor 2004), including the island of Sri Lanka (then called Ceylon), where several early writers described the practice of hunting and catching crocodiles (e.g., Bennett 1843; Sirr1850; Baker 1854; Tennent 1861; Clark 1901; Hornaday 1901; Wright 1907; Hagenbeck& Hoeven 1942).

During a recent review of the historical literature pertaining to the crocodiles of Sri Lanka, we came across some curious accounts of the use of human babies as bait to lure crocodiles in sport hunting on the island. We compile these records here, and review other records of the practice.

Babies as bait

Two species of crocodiles inhabit Sri Lanka: the Saltwater Crocodile Crocodylus porosus, which is largely restricted to the coastal areas of the south and south-west, and the Mugger C. palustris which occurs throughout the lowland dry zone (Whitaker & Whitaker 1979; Santiapillai & de Silva 2001; de Silva 2013). The historical distribution and abundance of both species was greater than today (Kelaart1852; Ferguson 1877; Deraniyagala1939), and, given that they were not legally protected until recently, hunting of the animals was also common (Deraniyagala 1930; Tutein-Nolthenius 1934; Ahlip1965). Among the many historical reports of hunting crocodiles on the island, the following accounts in early newspapers report the use of human babies as bait to lure crocodiles for hunting.

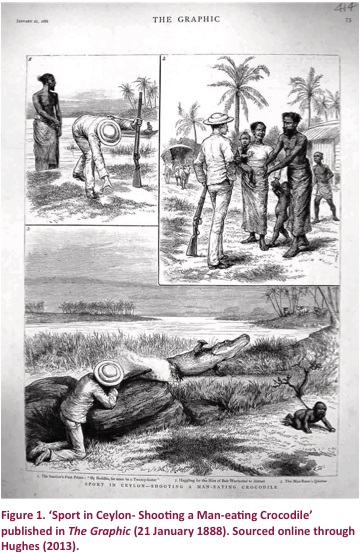

The Graphic, a London-based newspaper, included in its 21 January 1888 issue three interesting sketches of the method of using a baby to lure a large crocodile (Fig. 1). Captioned ‘Sport in Ceylon—Shooting a Man-eating Crocodile’, the figure depicts: (1) an European man estimating the size of a crocodile to be a ‘twenty footer’; (2) hiring a baby from the locals as bait, and (3).the concealed hunter shooting the crocodile that has been lured to the baby tied to a bush on the bank. The preferred bait is specified as ‘a chubby, rice-distended and squally infant’.

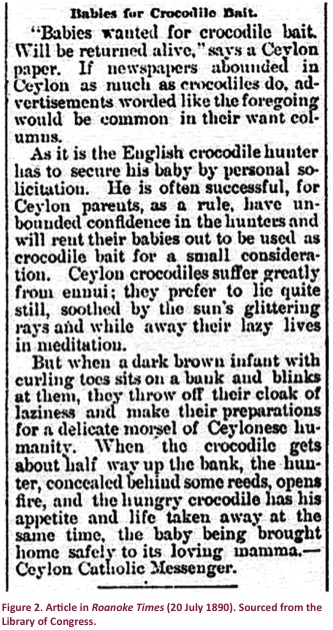

Several contemporaneous newspapers, including The Red Cloud Chief (6 April 1888), The Helena Independent (18 April 1890), Desert Evening News (29 April 1890), Roanoke Times (20 July 1890) and those cited below each contained a news item titled ‘Babies for Crocodile Bait’. They all referred to a newspaper advertisement captioned ‘Babies wanted for crocodile bait. Will be returned alive’ that was published in the Ceylonese newspaper Ceylon Catholic Messenger. Our attempts to locate the original article failed, hence the note which appeared in the Roanoke Times is reproduced here as Fig. 2. The notes state that Ceylonese parents have unbounded confidence in English crocodile hunters. They would rent their babies out to be used as bait to lure crocodiles for a small consideration, and it is not difficult for an English crocodile hunter to secure the bait (Mower County Transcript: 23 July 1890). The articles further mention that after the crocodiles had been attracted to the dark-brown infant on the bank, the hidden hunter would shoot the animal as it approaches the live ‘bait’. The sportsman would then secure the skin and the head of the crocodile, and the natives would make use of the rest of the carcass. Some report that, ‘The baby is taken home to its loving parents, to be used for the same purpose next day’. Several newspapers, including the Omaha Daily Bee (5 March 1888), Western Kansas World (30 June 1888) and Barton County Democrat(29 March 1888) referring to these reports, stated that ‘This way of securing crocodiles might be objected to by American mothers. The American infant imagination might be shuttered by the devouring gaze of a healthy saurian who hasn’t had his dinner; but we are creditably informed by certain English crocodile hunters that the average Ceylon infant displays a passive indifference to his advances, and the only thing which frightens him is the report of the gun’.

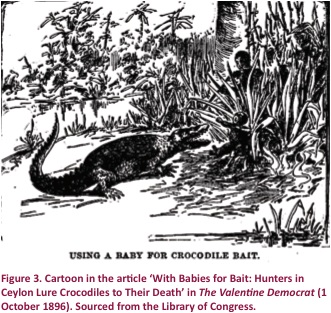

Possibly the same story reappeared in The Valentine Democrat (1 October 1896) which describes how ‘a nice, fat baby is tied by the leg to a stake near some pond or lagoon where crocodiles abound. Soon the child begins crying and the sound attracts the crocodiles within hearing distance. They start out immediately for the wailing infant…’. The writer further mentions that ‘So expert are many of the hunters that they do not shoot the alligator (correctly, the crocodile) until it has approached to within a few feet of the baby’. The article was accompanied by a sketch in which the hunter is positioned immediately next to the baby but concealed among the bushes (Fig. 3).

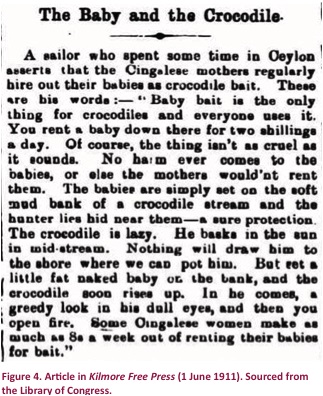

A third set of reports that appeared in American and Australian newspapers Cameron County Press(‘Babes and Bait’—12 December 1907), The Daily News (Perth, WA) (‘Babies as Bait!’—11 April 1908), The Columbian (‘Baby Bait for Crocodile’—2 July 1908), Healesvilleand Yarra Glen Guardian (‘Baby Bait for Crocodiles’—23 August 1910), The Southern Record and Advertiser (‘A New Use for Babies’—26 November 1910), Shiner Gazette (‘Use Live Babies as Bait’—26 January 1911), and Kilmore Free Press(‘The Baby and the Crocodile’—1 June 1911: Fig. 4), detail a sailor’s account of using babies to lure crocodiles in Ceylon. He states that Cingalese (= Sinhalese, some early western authors spelt this as Cingalese) mothers regularly (up to four times a week) hire out babies for two shillings a day (currency used in early British Ceylon until it was replaced by the Rupee in 1852. Currently a shilling would equal US¢ 8½, but its purchasing power was arguably much greater in early 1900s). He further mentions that ‘baby bait is the only bait for crocodiles and everyone uses it’. The sailor claims to have shot as many as four crocodiles with just one baby in a single morning and the babies are unharmed in the process. Similar to the account in Ceylon Catholic Messenger, this story states that human babies are the best bait to get the attention of crocodiles and lure them to the bank for shooting.

Records from elsewhere

Records of using babies as bait for crocodiles also exist elsewhere. The Richmond Dispatch (10 July 1894) and the Record-Union (1 September 1894) printed an article on ‘How British Sportsmen Hunt Crocodiles in India’ where an ex-officer of the British Army was quoted as saying, ‘We used to have a great sport in India going out after crocodiles with Hindu babies as bait’. He mentions that native women will flock to rent their babies for six cents per day and some would not even insist on a guarantee of their safe return (and that some crocodiles in fact got away with the ‘bait’). The officer claimed to have shot more than 100 crocodiles with just one chosen baby girl as bait. He added that he could not find an infant for rent to follow the same procedure in hunting an alligator in Florida, USA.

Anecdotal reports of the use of human babies as bait for crocodilians do exist, nevertheless, in American newspapers. In a compilation of records of the use of African-American babies as bait for alligators in the USA, Gilliam (2014) records that in 1908 the Washington Times reported that a keeper at the New York Zoological Garden baited ‘Alligators with Pickaninnies’ (a derogatory term for African-American children) and that ‘The alligators were coaxed” ‘into their summer quarters by plump little Africans’. The Oakland Tribune on 21 September 1923 contained the article ‘Pickaninny bait lures voracious gator to death’, where Villiers (1923) describes in detail the procedure of using black babies as live bait (for $2) and further states that ‘there is nothing terrible about it, except that it is spelling death for the alligators’. In July 1968, the Los Angeles Times ran an article about the baseball player Bob Gibson in which he mentions an inhabitant of Georgia stating that ‘Negro youngsters’ were used in baiting alligators (Chapin 1968). The use of African-American babies as live bait for alligators has been also used in American movie plots, including Alligator Bait (1900), The Gator and the Pickaninny (1900) and Untamed Fury (1947), and also used in postcards (Abagond2010; Hughes 2013; Gilliam 2014).

Melina da Fonseca Rorke in her book The Story of Melina Rorke, describes an incident where African babies were used by their fathers to lure crocodiles (possibly Nile crocodiles). She writes ‘…..in a few moments, though, the children who had previously been ignored, became the centre of attention; they were suddenly scooped up from the ground and carried swiftly down to the river bank in front of the screen where they were laid in the mud about 10 feet apart. To my unspeakable horror, I realised that those poor little piccaninnies were to serve as live bait for the crocodiles…..’(Rorke 1938). In this incident, a group of men has hunted the crocodiles with spears and have used several children and infants (possibly their own) as bait.

Discussion

Written records of crocodile hunts in Sri Lanka span thousands of years. Even the Great Chronicle of Sri Lanka, the Mahāvamsa, records that a man-eating crocodile at Gal-Oya was hunted down by King Rajasinghe II (1629‒1687 CE). Records from the 17thcentury onwards show that the Portuguese, Dutch and the British hunted crocodiles as sport and in order to remove ‘man-eaters’ (Haughton 1916; Deraniyagala 1939; Hagenbeck& Hoeven 1942; de Silva 2013). Hunting crocodiles for sport was banned in 1964 with the listing of both Sri Lankan species as protected species, but they nevertheless continue (illegally) to be hunted out of fear and in the hope of preventing future attacks (Somaweera& de Silva 2012) as well as for meat and hide (Madawalaet al. 2013; Samarasinghe 2014).

These early records are fascinating as recent island-wide surveys of crocodilians themselves, their attacks and human perceptions towards crocodiles in Sri Lanka, did not encounter any records or even folklore or myths referring to the use of humans as bait for crocodiles (de Silva 2010, 2013). The references to this practice on the island were published during the middle British period in Sri Lankan history (the British colonial period in Sri Lanka lasted from 1802 to 1948), in printed media abroad. However, a review of early, more-detailed literature on hunting and catching crocodiles in the island (Bennett 1843; Sirr 1850; Baker 1854; Tennent1861; Suckling 1876; Clark 1901; Hornaday 1901; Wright 1907; Haughton 1916; Deraniyagala 1939; Hagenbeck & Hoeven 1942), including those prior, contemporary and subsequent to the media records above, and communications with sociologists, historians, archeologistsat the University of Peradeniya (one of the leading research institutes in the relevant fields), has failed to uncover any additional records of human babies being used as bait. It is surprising that none of the more detailed accounts in the books and journals reported this practice indeed given that it appears to have been both common (e.g., some articles quote ‘baby bait is the only bait for crocodiles and everyone uses it’) and effective (e.g., the account in Richmond Dispatch states that as many as half a dozen crocodiles could come hurrying from as many different parts of a river towards a baby within five minutes of it being positioned) as claimed in the newspaper articles. It is also important to note that the frequency of reporting of these cases does not necessarily imply that the practice was common or widespread. Indeed, it appears that an article in one newspaper was picked up and reproduced by other newspapers, even at a much later date (e.g., after eight years in one case above), just as it does nowadays, albeit electronically and much faster.

However, using live dogs as well as dead animals (chicken, dogs, monkeys, cattle etc.) as bait to lure crocodiles was reported at several locations during our surveys, a practice that has its roots in early Ceylon. Ahlip (1965) reports the use of monkey meat as bait for Muggers and Clark (1901) states that crocodiles in Ceylon are most easily shot from points of ambush near the carcasses of cattle or a young ‘pariah’ dog (possibly referring to a stray dog), or a puppy that has been tied up at the bank. The yelping of the puppy is said to attract the crocodiles and bring them within easy shooting distance. Deraniyagala (1939) reported how live dogs were used to lure crocodiles, and the usage of living as well as dead animals as bait was a common practice (Rajakarurnnayake2000). Given that these authors explicitly cite the use of other live bait for crocodiles, it is surprising that they did not encounter any incidents in which babies were used as bait.

Many hunting strategies involve live bait to lure prey to the hunter, but very few involve using humans as bait. Among current examples are members of certain African tribes using their feet as lures to extract pythons from burrows (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kqVfgJrDYS0) and fishermen in the southern United States ‘noodling’ for large catfish offering their hands as lures (Salazar 2002). In both cases the hunter uses his own body as a lure, whereas in historical times hunters sometimes used other humans as bait to attract their prey. For example, African ‘coolies’ were used to lure lions for shooting during the construction of the Mombasa-Uganda railway in East Africa in 1898 (Mannix 1978). However, these probably involved adult humans rather than infants. Hence these anecdotal reports of using human babies as live bait in sport hunting constitute an important record in early hunting practices, as well as shining a new light on our colonial history.

References

Abagond, J. (2010). Alligator bait<http://abagond.wordpress.com/2010/08/11/alligator-bait/>. Accessed 5 May 2014.

Ahlip, T.C. (1965). Our tank crocodiles. Loris 10: 242–245.

Baker, S.W. (1854). The Rifle and The Hound in Ceylon. Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans.

Bennett, J.W. (1843). Ceylon and Its Capabilities. W.H. Allen & Co., London.

Chapin, D. (1968). Bob Gibson: Black man nobody wanted Until he was a hero” Los Angeles Times No. July 5, 1968.

Clark, A. (1901). Sport in the Low-country of Ceylon. A.M. & J. Ferguson.

Coningham, R.A. (1995). Monks, caves and kings: a reassessment of the nature of early Buddhism in Sri Lanka. World Archaeology 27: 222–242; http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00438243.1995.9980305

de Silva, A. (2010). Crocodiles of Sri Lanka: preliminary assessment of their status and the human crocodile conflict situation. Unpublished report to Mohamed Bin ZeyedSpecies Conservation Fund, Gampola, Sri Lanka

de Silva, A. (2013). The Crocodiles of Sri Lanka. Published by the author, 254pp.

Deraniyagala, P.E.P. (1930). Crocodiles of Ceylon. Spolia Zeylanica16: 89–95.

Deraniyagala, P.E.P. (1939). The Tetrapod reptiles of Ceylon. Vol. 1 – Testudinates and Crocodilians. Ceylon National Museum, Colombo.

Ferguson, W. (1877). Reptile fauna of Ceylon. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles.

Gilliam, G. (2014). Black history month: Black babies used as Alligator bait <http://georgeabouttown.squarespace.com/georgeabouttownblog/black-history-month-black-babies-used-as-alligator-bait232014s>. Accessed 5 May 2014.

Griffin, E. (2007).Blood Sport: Hunting in Britain Since 1066. Yale University Press.

Hagenbeck, J.G. & A.V.D. Hoeven (1942). Tussen olifanten en krokodillen: jachtavonturen op Ceylon, het tropische paradijs. Scheltens& Giltay, Netherlands.

Haughton, S. (1916). Sport and Travel. University Press, Dublin.

Hornaday, W.T. (1901). Two Years in The Jungle: The Experiences of A Hunter and Naturalist in India, Ceylon, the Malay Peninsula and Borneo. Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York.

Hughes, F. (2013). Black history moment: Black babies used as alligator bait. Lest we forget we are still oppressed<http://theobamacrat.com/2014/01/12/black-history-moment-black-babies-used-as-alligator-bait-lest-we-forget-we-are-still-oppressed/>. 30 April 2014.

Kelaart, E.F. (1852). Prodromus Faunae Zeylanicae: Being Contributions to the Zoology of Ceylon. Printed by the author, Colombo.

MacKenzie, J.M. (1997). The Empire of Nature: Hunting, Conservation and British Imperialism. Manchester University Press.

Madawala, M.B., A. Kumarasinghe, A.A.T. Amarasinghe & D.M.S.S. Karunarathna(2013). Current conservation status of Crocodylusporosus fromBorupana Ela and its hinterlands in Moratuwa, Sri Lanka. Proceedings of the World Crocodile Conference, Negombo, Sri Lanka, 242pp.

Mannix, D.P. (1978). The Wolves of Paris. eNet Press Inc.

Rajakarurnnayake, S. (2000). Crocodile killers use dogs as bait. Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter 19: 10–11.

Rorke, M.D.F. (1938). The Story of Melina Rorke, R.R.C. The Greystone Press, South Africa.

Salazar, D.A. (2002).Noodling: an American folk fishing technique. The Journal of Popular Culture35: 145–155; http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3840.2002.3504_145.x

Samarasinghe, D.J.S. (2014). The Human-Crocodile Conflict in Nilwala River, Matara (Phase 1). Young Zoologists’ Association, Sri Lanka.

Santiapillai, C. & M. de Silva (2001). Status, distribution and conservation of crocodiles in Sri Lanka. Biological Conservation 97: 305–318; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3207(00)00126-9

Sirr, H.C. (1850). Ceylon and The Cingalese; Their History, Government, and Religion. William Shoberl, London.

Smalley, A.L. (2005). ‘I just like to kill things’: women, men and the gender of sport hunting in the United States, 1940–1973. Gender & History 17: 183–209.

Somaweera, R. & A. de Silva (2012). Using traditional knowledge to minimize human-crocodile conflict and conserve crocodiles in Sri Lanka.Unpublished report to Chicago Zoological Society/ Chicago Board of Trade Endangered Species Fund.

Suckling, H.J. (1876). Ceylon: a general description of the island, historical, physical, statistical. Containing the most recent information. Chapman & Hall.

Taylor, A. (2004).‘Pig-Sticking Princes’: royal hunting, moral outrage, and the republican opposition to animal abuse in 19th and early 20th century Britain. History89: 30–48; http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.0018-2648.2004.00286.x

Tennent, J.E. (1861). Sketches of The Natural History of Ceylon with Narratives and Anecdotes. Longman, Green, Longman and Roberts, London.

Tutein-Nolthenius, F.C. (1934). Exploitation of wildlife (Ceylon). Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 37: 219–229.

Villiers, T.W. (1923). Pickaninny bait lures voracious gator to death. Oakland Tribune No. September 21, 1923, 11pp.

Whitaker, R. & Z. Whitaker (1979). Preliminary crocodile survey-Sri Lanka. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 76: 66–85.

Wright, A. (1907). Twentieth Century Impressions of Ceylon: Its History, People, Commerce, Industries, and Resources.

Asian Educational Services.

August 12th, 2018 at 3:43 pm

“……, the baby being brought home safely to its loving mama – Ceylon Catholic Messenger”

The above quote from the news paper tells me in which part of the country this practice was prevalent and who were the people that trusted the sudda so much.