Karunananda of Sri Lanka: The Courageous Loser Who Won Hearts at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics

Posted on August 5th, 2021

Keiji Morita, staff reporter, The Sankei Shimbun

Everyone shouted as if they were cheering for their own country’s athlete. Some of them watched him in awe with their eyes shining with tears.

In 1964, an unknown Olympian from a foreign country took Japan’s breath away.

The Olympian became known in Japan as Uniform Number 67,” the runner from Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) who didn’t abandon the race despite coming last in the men’s 10,000 meters at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics.

His story touched so many hearts that it was later included in Japanese elementary school textbooks. Fifty-seven years after the race, the runner’s granddaughter is now working in Japan, the host country of the Summer Olympics for the second time.

Japan is my second homeland. Maybe this is fate,” she says. She was cheering for the men in the 10,000 meters on the evening of July 30 through her TV, with the image of her grandfather’s heroic figure in her mind’s eye.

Oshadi Nuwanthika Halpe, 29, is a care worker at an elderly care facility in Shibukawa City, Gunma Prefecture. Oshadi’s mother would tell her stories about her grandfather as she grew up, about why he had been handed down as a hero in his home country of Sri Lanka.

I was told that he was devoted to housekeeping and his children. His mantra was, ‘You must finish what you started.’”

Uniform Number 67

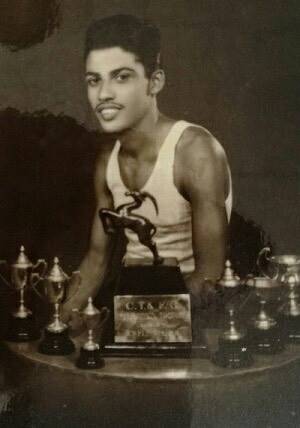

Her grandfather’s name was Ranatunge Karunananda. On October 14, 1964, Karunananda stood in front of 70,000 spectators at the Japan National Stadium as the Olympian who held Ceylon’s national record for the men’s 10,000 meters.

Karunananda’s story was published under the title Uniform Number 67” in the textbook New Japanese for Fourth Grade of Elementary School by Mitsumura Tosho Publishing, which begins like this.

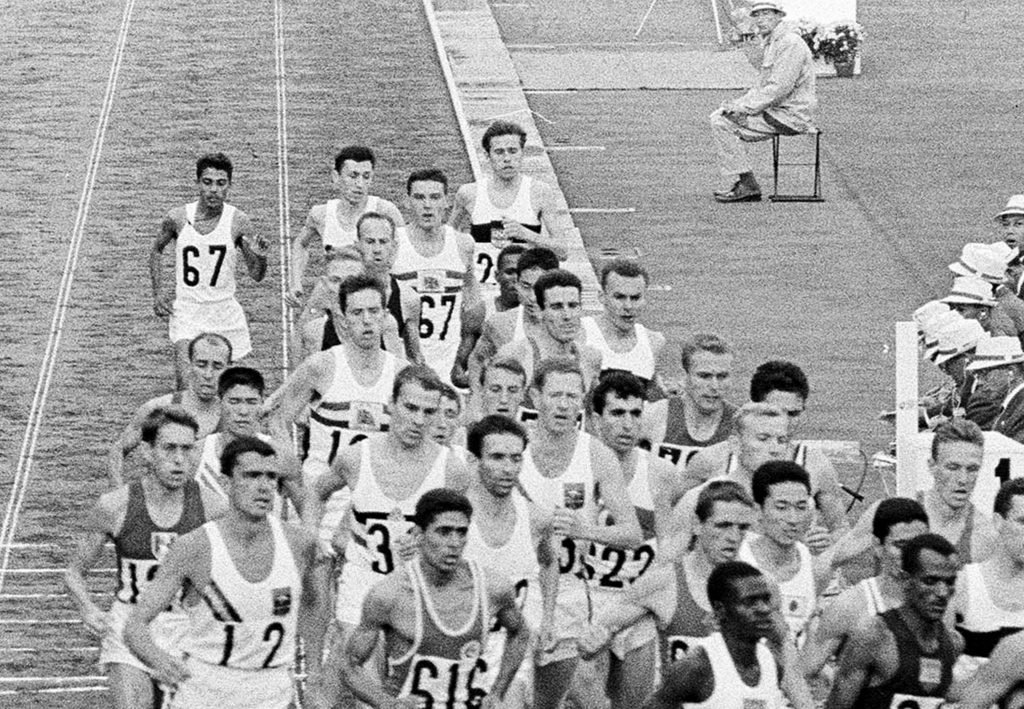

It was 4:05 pm. The roar died down to a mumble, and the spectators turned their eyes to the thirty-eight runners who were lined up at the starting line. The pistol sounded, and the runners took off at once.”

The race, in which Japan’s Kokichi Tsuburaya finished in 6th place, was a grueling 25 laps around a 400-meter track. Nine of the 38 runners had to give up halfway through the race. When the runner who was thought to be last crossed the finish line, everybody assumed that the race was over.

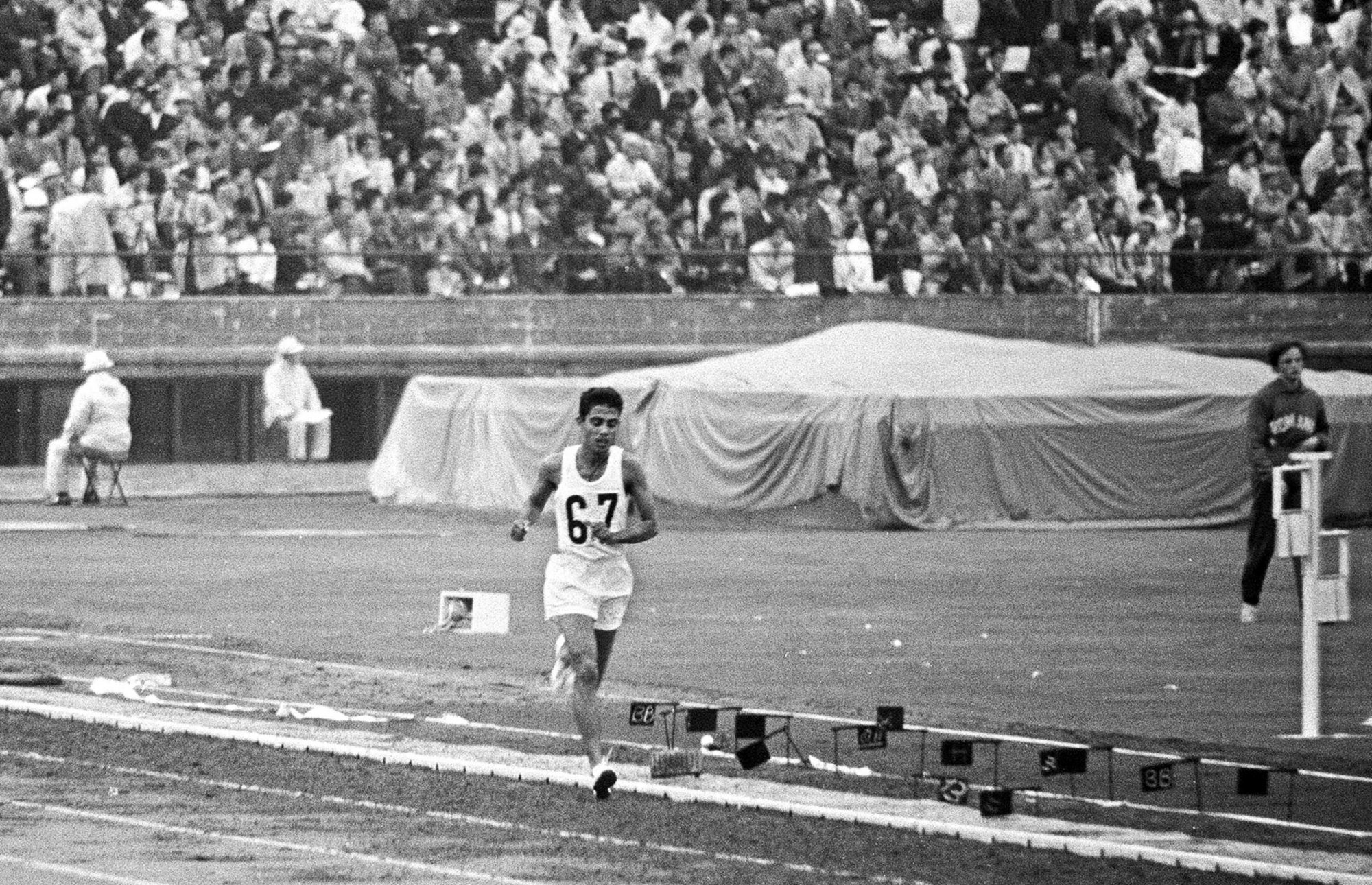

But Uniform Number 67 didn’t stop running. Under the jeers and boos of the crowd, Karunananda kept pushing himself, one lap behind the others. He was in great agony, holding his side as he ran, but the jeers and boos soon turned into cheers.

Everyone shouted as if they were cheering for their own country’s athlete. Some of them watched him in awe with their eyes shining with tears.

Karunananda was showered with applause as he crossed the finish line.

He afterwards said, I have a little daughter back home. When she grows up, I will tell her that her father went to the Tokyo Olympics and ran till the end even though he lost the race.”

Despite being ill for about a week before the race, Karunananda didn’t give up, no matter how much he lagged behind. The reason behind his determination was that his home country Ceylon was suffering from a bad economy, and it put a huge strain on the country’s financial resources to send athletes to the Olympics.

Uniform Number 67” appeared in Japanese language textbooks in 1971 and from 1974 to 1976. The publisher had a 50% market share at the time. An English translation of the text has also been available in junior high school English textbooks since 2016.

Ten years after the Olympics, Karunananda died in a water accident at the age of 38. In Sri Lanka, the story of his legendary race has been retold by the media before every Summer Olympics for 57 years.

Inspiring the Granddaughter He Never Knew

Oshadi is the daughter of Karunananda’s little daughter.” She studied geography at the University of Colombo, then came to Japan in the spring of 2016 to study disaster prevention at graduate school. She was surprised to learn that her grandfather’s legacy still lived on in the hearts of the Japanese people.

It’s as if my grandfather is still alive in Japan,” she says.

Oshadi studied at a Japanese language school in Gunma Prefecture but felt her vocabulary was too lacking to study at graduate school. Although she graduated in the spring of 2018, she felt lost about her future. Oshadi was beginning to consider returning to Sri Lanka when a friend sent her an online video of her grandfather running.

You must finish what you started.” Her grandfather’s words started to make sense when she saw the video. She had chosen to become a care worker because of her grandmother (Karunananda’s wife), who was bedridden in her hometown.

Oshadi studied for another two years at a college which specializes in health care skills in Shibukawa City. In the spring of 2020, she began working as a care worker at an elderly care facility (where she currently works). She married a Japanese man she met there.

Her dream is to acquire nursing skills in Japan and pass them on to future generations in Sri Lanka, where specialist long-term care is still in short supply. I don’t know how many years it will take, but I want to go back one day to pass on what I have learned. I think it’s my grandfather’s way of teaching me how to give back to my country.”

Olympic Dreams Live On

The coronavirus pandemic has been a big concern for the Tokyo Olympics. Oshadi had considered going to the Japan National Stadium to experience the atmosphere of the Games. But she decided instead to cheer for the athletes on TV because she knew the weight of the responsibility of taking care of the elderly as a care worker.

One day, I hope to see the place where my grandfather ran with my own eyes. My mother also says she wants to visit at least once before she dies, so I’d like to go with her then.”

The men’s 10,000 meters, the race Karunananda bravely lost, was held at the newly reconstructed Japan National Stadium on the evening of July 30. The last runner to complete the race was Kieran Tuntivate of Thailand, who also finished what he started.

(Read The Sankei Shimbun story in Japanese at this link.)

Author: Keiji Morita, staff reporter, The Sankei Shimbun