Rupee devaluation: Is it to save the country, exporters or the opposition?

Posted on October 16th, 2022

By Luxman Siriwardena and Chanuka Wattegama Courtesy The Sunday Times (LK)

Published on 17th April 2011

The main opposition party has recently demanded a devaluation of the Sri Lankan Rupee (LKR) to ‘increase exports’ and ‘boost the economy’. This process, claims our ‘government-in-waiting’, is the assured remedy to increase the share of exports in the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), which, according to them has fallen to ‘miserable levels’.

As almost all policy decisions, a currency devaluation too has a positive and a negative impact. This is an attempt to present a balanced view. To begin with, there is nothing new in this call. For many decades local currency devaluation has been prescribed as a panacea to most economic ills of developing nations by the IMF and neo classical text book economic pundits. Of course, exporters love a weaker LKR. It improves their short term competitiveness as well rupee gains. Just like a peasant in hard times anticipates the government to subside his fertilizer costs, which will in turn lower his vegetable prices in a competitive market, the exporters too eternally look for a helping hand from the government.

The opposition becomes their typical messenger. The advantage of sitting across the floor is that one can take the credit for a policy intervention by the beneficiaries without risking the wrath of the losers. That could well be the raison d’être behind this proposition. It would be too naïve to assume sincerity. After all, oppositions love to see governments losing popularity, not gaining.

LKR devaluation was not a high priority of the short-lived government of the current opposition from 2001-2004. For this period LKR only fell from not more than one tenth of a US cent, which can hardly be called devaluing. Regaining Sri Lanka, the policy document of the times (still downloadable from multiple sites including that of the External Resources Department) neither mentions the terms ‘devaluation’ or even ‘Rupee’ if it were not to denote a figure, though it emphasizes the importance of increasing exports and expanding access to overseas markets to reach the planned 10 percent growth rate. Why preach policy changes one does not practice oneself?

The opposition, like anyone with the basic commonsense, knows the government has no compulsion to devalue LKR at this juncture. The probability of a major devaluation of 25% is almost nil. The immediate focus of the government is growth. Sri Lanka is enjoying a healthy and consistent growth in its economy. Per Capita GDP (real) of $1,000 in 2005 has more than doubled to $2,400 in 2010, with an unprecedented growth rate in the post-independence period.The aim is $4,000 by the year 2016. This is no reason for complacence; we will still be below Thailand and Tunisia, but fourfold increase within a mere 10 years will be no small achievement.

Sri Lanka, except the micro state Maldives, will be the first South Asian nation to reach this milestone. Every cog, nut and bolt in the system is tuned to achieve this growth. The government certainly will not welcome any deviation from its blueprint.

What can devaluation possibly achieve?

What were our past experiences?

First, a word about the choice of terms. Though incorrectly used synonymously to denote a drop in currency value with respect to other currencies, ‘devaluation’ and ‘depreciation’ have different implications. ‘Devaluation’ means official lowering of the value of a country’s currency within a fixed exchange rate system, by which the monetary authority formally sets a new fixed rate with respect to a foreign reference currency. In contrast, depreciation is used for the unofficial decrease in the exchange rate in a floating exchange rate system. Under the second system central banks maintain the rates up or down by buying or selling foreign currency, usually USD.Under its previous fixed value system, LKR has undergone two major devaluations. First was in 1965, under the Dudley Senanayake government. The immediate reaction of the then opposition was to coin a new term ‘rupiyala baaldu karanavaa’ underlining the negative bearing of the move. It was further devalued in 1977, when the newly elected, market oriented government under the leadership of President J. R. Jayawardena found no other way to bridge the huge gap between the nominal and real exchange rates.India’s experience is not too different. India had first devalued the Indian Rupee (INR) in 1966. The continued trade deficits of increasing effects, since 1950s, have made foreign borrowings impossible. The situation was further deteriorated by the massive defence spending of the Indo-Pak war of 1965.

India has also lost some of its financially important foreign allies who backed Pakistan. The nationwide drought was the last straw that forced the devaluation. In 1991, on the second time, it wasn’t a war but the balance of payment issues that forced the INR devaluation.The exchange reserves had dried up to the point that India could barely finance three weeks’ worth of imports. Dr. Manmohan Singh, as the finance minister in Narasimha Rao’s government saw no other alternative than a significant devaluation of INR. None of these devaluations was pre-planned. They were extreme measures forced by the conditions. The objectives too were not to improve the exports, but to ease the immediate tensions in the economy. They wouldn’t have simply happened under normal circumstances.Pro-devaluation economists are correct in saying a lower LKR improves our competitiveness in the short run. We fully agree. It is basic economics. That is why China pegs Yuan (CNY) to USD, despite the pressure not to. The problem is devaluation is no free lunch; it comes with a massive price tag.

To take the most straightforward example, devaluation will immediately skyrocket all loans in foreign currency, further burdening a debt ridden nation. So the question is not whether devaluation improves exports, but whether it does so to a level that justifies the price tag.Let us take this simple illustration. The on-going market price of a lunch packet near Sethsiripaya, Battaramulla is LKR 100. At LKR 110, one will sell a less number of packets, and at LKR 200, may be none. Anything below LKR 100 makes the product competitive and increases the sales.

This does not mean a vendor can price tag a lunch packet at LKR 50. It will be below the production costs and irrespective of the sales, there will be no gain. The more he sells the more he loses.

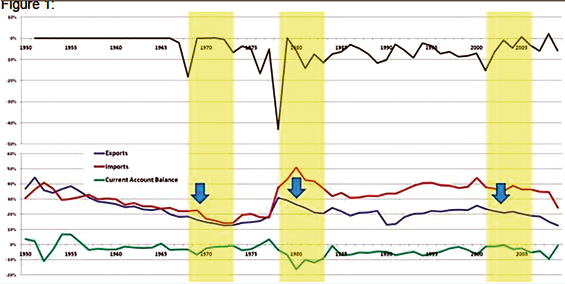

This is the age of policy based on evidence, not just on theory. Does the past evidence support the hypothesis of LKR devaluation improves the exports? The top half of Figure 1 shows the annual effective LKR devaluation rates since 1950. The bottom half shows the variation in imports, exports and current account balance, taken as percentages of GDP of the respective year, to maintain uniformity. Please see the highlighted five years periods after three significant devaluations. Do we see an improvement in exports or current account balances?Then to gradual devaluation. In 1990 one USD was LKR 40. This rate has nearly trebled to 115 by 2010. Do we see a related growth either in exports or balance of payments during this period? There can be multiple explanations why previous LKR devaluations didn’t work. We give four below. There can be others.For some export commodities the local value addition is limited to labour. When we import raw material just to be processed here, the devaluation of LKR is of little use as the competitive gain gets partially offset by the increase in the cost of raw mterials.The price elasticity of the demand of some of our export products is low. Two good examples are cinnamon for which we have a significant global market share and high-end apparel products. Price variations will have little impact on the sales of these products.The positive outcome of devaluation depends largely on the significant reduction in budget deficit, maintaining prudent macroeconomic policies and stabilised wages. These are killer assumptions to make, not just in a developing country, but sometimes developed as well.The devaluation of LKR naturally increases the cost of living. Any devaluation is associated with an immediate rise in imported food, fuel and other input prices. As we know by experience this puts immediate pressures not only on households but even local industries. It eventually forces the government, goods and services producers for both local and export markets to increase wages of labour, offsetting the gains.The last one can mean far reaching negative impact. The inflation that will certainly follow the devaluation will lead to the increase of prices, wages and inflation. This is what the economists call a ‘devaluation/inflation spiral’. This ‘wages chase prices and prices chase wages’ situation will have the opposite impact on the industry to the intended.Going back to the previous example, we hope exporters and neo classical economists come out of the mentality of dry zone peasants who expect the government to subsidize their fertilizer. The exports are important, no doubt, in the economic growth of a country but we reach nowhere by perennially waiting for a weaker LKR.A more rational approach is to increase productivity and product quality. Unless we improve product quality and introduce product diversification devaluation will not help exporters in the long run. It might perhaps help the opposition in the next elections, though.(Mr Siriwardena, holds an MA in Economics from Vanderbilt University and Mr Wattegama an MBA from the University of Colombo. They are independent policy researchers and can be contacted at lankaecon@gmail.com).

Source: Author calculations based on data from Central Bank of Sri Lanka |