Beyond praise and blame

Posted on June 13th, 2023

Malinda Seneviratne

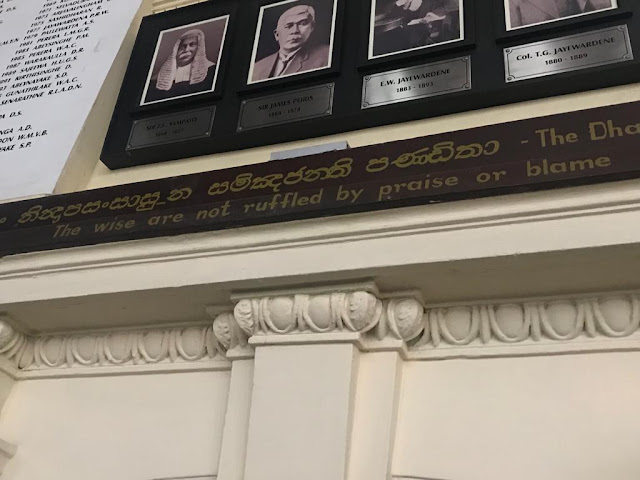

The first time I encountered the word ‘ruffled’ was in the main hall of my school. The walls were lined with adorned with photographs of distinguished alumni and under each set there was an inspirational quote. This was one: ’The wise are not ruffled by praise or blame.’

It was much later that I learned the word ‘equanimity’ and that this is a quality that is good to cultivate for it helps in dealing with the vicissitudes of life.

Praise and blame can be levelled at us, people we love, institutions we identify with and even the faiths we subscribe to. We have seen a lot of the last of these three recently. It’s not just what’s said but the way it is said. Tests us.

My friend Sugath Kulatunga, by way of response, recommends reflection on the Brahmajala Sutra.

Here’s the background. It is the first of 34 sutras in the Dīgha Nikāya (the Long Discourses of the Buddha). Once, while the Buddha was traveling with his disciples between Rajagaha and Nalanada, a Brahmin named Suppiya, traveling in the same direction with his apprentice Brahmadatta, tailing the convoy, had uttered disparaging words about the Enlightened One. Brahmadatta, in contrast, had praised the Buddha.

Later, the disciples who had heard all this, had related the exchange to the Buddha, who then proceeded to offer advice with respect to dealing with criticism and praise. The sutra is quite elaborate and covers many things, but the following passages posted by Sugath makes for much reflection:

‘Monks, if anyone should speak in disparagement of me, of the Dhamma or of the Sangha, you should not be angry, resentful or upset on that account. If you were to be angry or displeased at such disparagement, that would only be a hindrance to you. For if others disparage me, the Dhamma or the Sangha, and you are angry or displeased, can you recognize whether what they say is right or not?’

The disciples answer in the negative.

‘If others disparage me, the Dhamma or the Sangha, then you must explain what is incorrect as being incorrect, saying: That is incorrect, that is false, that is not our way, for that is not found among us.” But, monks, if others should speak in praise of me, of the Dhamma or of the Sangha, you should not on that account be pleased, happy or elated. If you were to be pleased, happy or elated at such praise, that would only be a hindrance to you. If others praise me, the Dhamma or the Sangha, you should acknowledge the truth of what is true, saying: That is correct, that is right, that is our way, that is found among us.”’

If indeed response is warranted, it should be founded in reason, in compassion and framed by equanimity. It is not unkind.

Of course, there is no guarantee that the person or persons, organised or otherwise, would accept logic and reason, particularly if the intent to insult, vilify and in other ways disparage, is a particularly malicious fixation. Still, even this does not warrant anger, resentment or agitation of any kind on the part of the receiver. If indeed one does get angry, resentful and agitated, it would be a hindrance to self, the doctrine one subscribes to and the collective one identifies with. It detracts, just as the insult amounts to an insult of the insulting individual, the doctrine in whose name the insult is made and the congregation the insulter identifies with.

The elaboration of these beliefs is very detailed, focusing on how the beliefs (faiths) come to be and the way they are described and declared. The Buddha, in the Brahmajala Sutra, elaborates on how beliefs or faiths come to be and the ways in which they are described and declared. The danger lies in clinging to beliefs because this indicates an inability to escape from desire, hatred and ignorance. Such individuals get entangled in the net of samsara while those who are open to perceiving the eternal verities and therefore are not perturbed by praise or blame are less likely to be captured and confined thus.

A corollary could be obtained. Criticism is best engaged with logic. The criticism, if valid, could inform, educate and persuade further reflection. Again, an open mind is required. Again, a refusal to be angered is required. Again, humility is a precondition. In the very least, even if the intent is vile, one’s peace of mind would not be compromised. The vilifier would be left to deal with the vilification.

Easy to say, ‘be wise,’ so much harder to acquire wisdom and act and speak accordingly. The Brahmajala Sutra, in which the Buddha elaborates on precepts, is a guide to being that would not detract from any doctrine or the practices of the relevant devout.