A transparent scrutiny of the Adani Mannar Wind Project

Posted on November 10th, 2024

Asanka Perera

The recent article ‘The Valid Reasons Why Adani’s Mannar Project Should be Cancelled’, criticizing the Adani Mannar wind energy project misses key facts and context. As Sri Lanka furthers its renewable energy ambitions, it is important to scrutinise the project, and more so to provide a fairer and balanced perspective.

- Unfounded claims of procedural irregularities in awarding the Project

The claims of procedural irregularities in awarding the Adani Mannar wind energy project are unfounded. The project was considered as part of Sri Lanka’s ‘Fast Tracking of Investments’ process, for which the Cabinet of Ministers granted approval to enter into an MOU with Adani Green. The Ministry of Finance’s notification clearly states that in cases where the decisions of the Cabinet Appointed Monitoring Committee for Investments (CAMCI) prevail, there is no need for a tendering process. Furthermore, the project fully complies with the provisions of the Electricity Act, as it has received Cabinet-level approval as a government-to-government (G2G) initiative and has been granted approval by the Public Utilities Commission of Sri Lanka (PUCSL) under the relevant sections of the Act.

The project also forms part of Sri Lanka’s Long-Term Generation Expansion Plan 2023-2042 approved by PUCSL. Sri Lanka has recently approved other single-bidder, single-location renewable energy proposals following a similar process of technical evaluation by a project committee and tariff negotiations by the Cabinet Appointed Negotiation Committee (CANC), which was also followed for Adani’s project. In addition, the proposal complies with the recent MOU between India and Sri Lanka on renewable energy cooperation, allowing participation from both private and public sectors.

Evaluating projects based on Indian regulations is illogical.

The argument to evaluate Sri Lankan projects based on Indian regulations and standards is illogical. The Indian electricity sector provides significantly more incentives to private developers, such as exempting renewable energy projects from the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) process, which reduces implementation timelines by 1-2 years compared to Sri Lanka. Additionally, India’s investment-grade rating allows for easier access to competitive external funding, and the government also provides private players with access to state-owned land on a sub-lease basis without constraints on mortgaging. These factors, which are not available in Sri Lanka, enable faster project approvals and implementation in India.

Besides, the regulatory bodies in India, such as the Central Electricity Regulatory Commission (CERC) and State Electricity Regulatory Commission (SERC), are empowered to adopt tariffs discovered through competitive bidding processes, even if those tariffs are higher than typical levels. Evaluating Sri Lankan projects solely based on Indian standards would be an oversimplification and fail to account for the unique regulatory environment and investment policies in Sri Lanka.

- No excessive or risky precedent in Adani’s Wind Tariffs

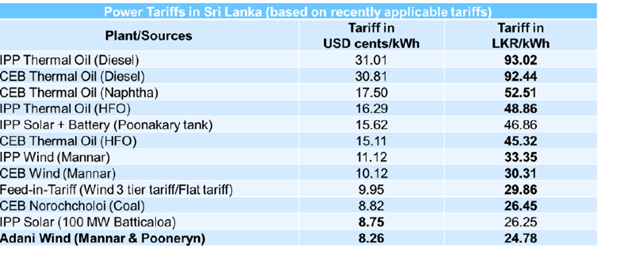

There is no excessive or risky precedent being set by the tariffs for Adani’s wind energy projects in Mannar and Pooneryn. In fact, the tariffs for these projects are the lowest wind energy tariffs in the country. This information can be verified from the data available on the Public Utilities Commission of Sri Lanka (PUCSL) website.

Source: PUSL Website

The claim that Adani’s tariff of $0.0826/kWh is significantly higher than the typical wind tariffs in India is an invalid comparison.

Comparing tariffs solely based on the Capacity Utilization Factor (CUF) or a mathematical formula for wind energy availability is an oversimplified and illogical approach. The Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) for a wind project depends on multiple factors, including the capital cost, cost of raising funds, tenure of the Power Purchase Agreement (PPA), and operational and maintenance (O&M) costs. It is important to note the PPA tenure in Sri Lanka is 20 years, whereas in India it is 25 years, allowing for longer asset ownership and operation. Furthermore, wind power assessment is a scientifically rigorous process, taking into account the installed and planned wind power capacity in the vicinity, rather than a mere mathematical formula analysis.

The comparison of Adani’s tariffs in Sri Lanka with wind energy tariffs in Gujarat, India, is a non-logical and flawed approach. The wind energy potential and resource availability in Gujarat’s largest renewable energy sites are similar, and in some cases even higher, than in Mannar. If the Sri Lankan government has access to the tariff information from India, the logical step would be to consider procuring wind power directly from India – now that the SL-India power transmission corridor is reportedly in the works— rather than delaying the local projects and demanding that Sri Lankan developers reduce their tariffs to unrealistic levels, such as $0.03/kWh. Thus, it would be an unfair and unjustified expectation, considering the unique factors and constraints faced by the Sri Lankan renewable energy sector.

- Comparison with IRENA data requires nuance.

The article’s comparison of the Mannar project’s tariff to the global average Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) for onshore wind as reported by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) is an oversimplified and flawed approach. IRENA’s global LCOE data does not account for the current inflationary pressures, the cost of borrowing, or the land acquisition costs, unique to each country’s context. Therefore, making a direct comparison between the Mannar project’s tariff and IRENA’s global averages is not a logical or accurate method of evaluation.

If the author is referencing IRENA data, a more appropriate comparison would be to the LCOE for the ‘Other Asia”’ region, where Sri Lanka’s costs would likely be captured, rather than the global average. Focusing solely on the global or Indian averages, the argument appears to be twisted to favour certain investors or local players in the country. It also raises questions about the objectivity and fairness of the criticism, especially when similar comparisons are not applied to evaluate the 8+ cents per kWh tariffs for solar projects approved in Sri Lanka. Meaningful analysis requires a nuanced, context-specific approach considering the unique factors influencing renewable energy costs in Sri Lanka, rather than simplistic global benchmarking.

- Selective environmental concerns

The article’s claims about the Mannar project site’s environmental issues are questionable, given the existence of similar renewable energy projects in the same region. If the site was truly problematic, it is illogical that the government has already implemented a 100 MW wind farm, is conducting a 50 MW tender, and approving smaller 5 MW IPP projects there.

Moreover, the article fails to acknowledge that the Adani project has undergone a comprehensive Environmental Impact Assessment, similar to the one for the CEB’s 100 MW wind farm. Indicative environmental concerns have been evaluated and mitigated.

Ignoring the existing projects and the EIA process, the article presents an inconsistent and biased argument. The selective application of environmental standards undermines the credibility of this criticism.

- Substantial cost savings and reduced fossil fuel dependence

At 8.26 cents per kWh, Adani’s wind energy will significantly undercut the country’s current oil and coal-based generation, which averages over 14 cents. The pricing differential will enable Sri Lanka to reduce its annual power generation costs by approximately $80 million.

Moreover, the country spends around $300 million yearly on imported oil and coal for electricity. Incorporating Adani’s wind project will save over $200 million in annual foreign exchange outflows, greatly enhancing energy security and economic stability. The cost-effective, renewable investment aligns with Sri Lanka’s energy diversification and decarbonization goals, presenting a strategic opportunity to transition towards a more sustainable and self-reliant future.

- Consequences of not implementing the Adani Project

Overlooking the broader implications, the article’s criticisms fail to recognize the significant repercussions of not implementing the Adani Mannar wind project.

Firstly, where will Sri Lanka attract over $1 billion in much-needed FDI for large-scale renewable energy, if not from investors like Adani? Domestic sources alone cannot finance these critical investments. Can Sri Lanka hope to achieve its sustainability goals — 70% RE generation by 2030 and net zero by 2050 – without such large RE projects? Over the next 25 years, SL’s power demand will grow at an annualized rate of ~5% and to meet our sustainability objectives, by 2050, we will need to add ~7,000 MW of fresh RE capacity. Do we have a blueprint to meet such a target?

In addition, without the Adani project, consumers will continue bearing the higher costs of fossil fuel-based generation, averaging over 14 cents per kWh, compared to the 8.26 cents offered. It would also burden the country with an extra $80 million per year. Besides, scrutinizing this strategic investment’s tariffs risks setting a dangerous precedent, leading to litigation against other high-cost projects and disrupting energy plans.

Rejecting the Adani project would deprive Sri Lanka of transformative FDI, prevent electricity cost reductions, and jeopardize meeting the country’s pressing energy needs – consequences detrimental to its economic and energy security. If this project doesn’t fructify, would any other large foreign investor ever look at Sri Lanka?

While the original article raises important points, it takes a narrow view and lacks a comprehensive understanding of the project’s context and potential benefits. The Adani Mannar wind energy project can be a significant contributor to Sri Lanka’s renewable energy goals, economic growth, and sustainable development. What is required is addressing valid concerns through rigorous analysis and stakeholder engagement, ensuring the project serves as a model for future investments driving Sri Lanka’s prosperity.