“SETTLER COLONIALISM” AND TAMIL EELAM Part 5Ca

Posted on November 22nd, 2024

KAMALIKA PIERIS

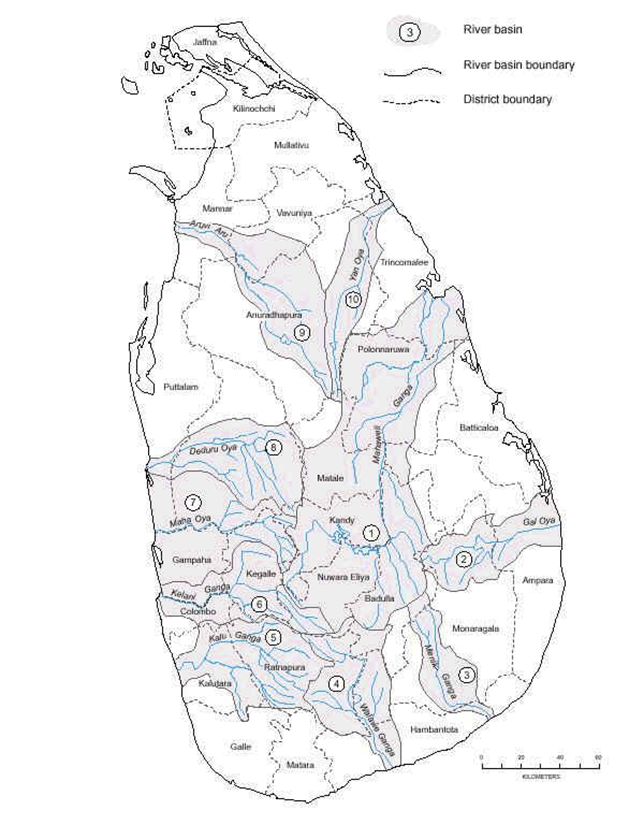

Gal Oya starts in the hill country east of Badulla and flows through the south east of Sri Lanka passing Inginiyagala and flows into the sea 16 km south of Kalmunai.

The idea of using Gal Oya for development was first suggested in the late 1930s. A technical survey on harnessing the development potential of the Gal Oya catchment was conducted in 1936. A more detailed ‘Gal Oya Development Plan’ was formulated in 1946. The Gal Oya Development Board was appointed in 1949. It was modeled on the Tennessee Valley Authority and the Damodar Valley Corporation, but these were giant corporations, unlike Gal 0ya.

The Gal Oya Irrigation and Power Project was inaugurated on August 24, 1949. Irrigation engineer W. T. I. Alagaratnam carried out the preliminary surveys and investigations. He later became the first Ceylonese Director of Irrigation (1952-1955). Preliminary designs and estimates were prepared by Designs & Research Engineer D. W. R. Kahawita assisted by Designs Engineer, V. D. Kothare and Actg. Designs Engineer V. N. Rajaratnam.

Kahawita took the designs to the consultants, at Denver, Colorado, USA. The consultants, International Engineering Co were greatly impressed by the complete and comprehensive set of drawings, soil tests, gauge readings and other information needed to design the project, provided by Kahawita and his team. Kahawita participated in the Denver design team’s work and was a decision maker in the project, said analysts. [1]

Gal Oya was Sri Lanka’s first, much hyped, development project of the post-independence period. It was a multipurpose project, serving Agriculture, Irrigation, Flood Control, Domestic Water Supply and Hydro Power.

The Gal Oya scheme was located some 150 miles from Colombo, in a region that had previously been jungle, sparsely populated by slash-and-burn cultivators. The valley had the air of being sealed off. It was situated in the deep interior and seemed inaccessible because of poor roads and transport.

Construction work began in March 1949. Modern machinery as well as elephants were used. Machinery removed the top soil as well as the trees. Large swathes of land had been dozered” bare. [2]

Work on the Left Bank started in 1951, Right Bank in 1957. Headworks were completed in 1951 and the water sent out. The project created new water bodies, but also incorporated existing tanks such as Kondavattavan, Valathippiddy, Veeragoda, Chadayantalawa and Irakkamam. A 10 MW hydro power plant was built.

Gal Oya project created a reservoir at Inginiyagala. The catchment area of the reservoir was in the Uva Province, but the reservoir benefited those living in the Eastern Province, observed analysts. The reservoir, Senanayake Samudra, had a capacity of 979 million cubic meters. Gal Oya National Park was declared in 1954 to protect the reservoir’s catchment area.

Immediately below the dam there were three main channels that control the delivery of the water the Right Bank (11,741 ha), the River Division (8,502 ha), and the Left Bank (16,328 ha).

The main reservoir was completed in 1960, and the full irrigation system transferred from the Gal Oya Development Board to the Irrigation Department. Its combined irrigated area made Gal Oya the largest contiguous irrigation system in Sri Lanka.[3]

Rice production was a priority at Gal Oya because 70% of the rice was imported. [4] The project would provide irrigation for 70,000 acres of new paddy land. Gal Oya acquired a huge rice mill, to assist in processing rice.

Provision was also made for cultivation and marketing cash crops by agricultural organizations. There was also a tile factory and a sugar factory at Gal Oya. The sugar factory was an utter failure, said analysts. The local farmers, unused to sugar cane cultivation, were never able to supply more than 18% of the factory’s requirements

The project functioned from 1951 onwards, garnering both praise and criticism. In 1966 the Dudley Senanayake government appointed a Committee to Evaluate the Gal Oya Project. The committee stated that from a purely cost/benefit point of view the project was a failure. But from colonization, paddy production point of view the project was successful. .[5]

The Gal oya scheme was also a colonization scheme, providing land to the landless. Gal Oya was sparsely populated, much of it was jungle. The jungle area was developed and people brought in and settled. First preference was given to people from the Eastern province. There were no applicants.[6]

Tamil Separatist Movement charged that Sinhala colonists were brought into the traditional homelands of the Tamils”. K.M. de Silva said that Gal Oya and most of the other major colonization schemes of the Eastern Province were located in areas which were either the sites of remnant Sinhalese villages or were jungle. For example, the Sinhala farmers were given land in Wewegampattu, which was a Sinhala area. [7]

The number of families settled from 1951 – 1953 were: from Batticaloa district 852 families, Kandy 213, Kegalle 275, Uva 250, Hambantota 175. By 1962, 6000 families were settled in over 40 villages. 2250 families were from the Batticaloa area. 3750 families came from other parts of the country.

S.J.Tambiah said about 50 percent of the settlers came from Eastern Province. They were Muslims and Tamils. This group also included Veddahs. The other 50% came from outside Gal Oya. About 25% of this second category came from from the Central Province, the majority being from the Kandy and Kegalle districts. The balance 25% came from Southern, Western, and Sabaragamuwa provinces, and they were all Sinhalese. [8]

Jayasuriya looked at the period 1951-1962. He said initially 15 villages, each with about 150 families were occupied by 2 categories of people .The first category were settlers from the area including Veddahs. They were the first to be settled in Wavinne and Paragahakelle in 1951. They were hunters and chena cultivators and they found it difficult to adjust to their new surroundings.

The second category was people from East Coast villages around Kalmunai. They were not interested in changing their traditional methods of livelihood. Their land produced only about 25 bushels of paddy per acre.

The most successful were those from Kandy and Kegalle. 25 villages, each with about 150 families, were occupied by settlers from Kandy and Kegalle in 1955/1956 . They were allotted 1 acre of highland & 3 acres of paddy land. They were the most enthusiastic . They used fertilizers and improved methods of cultivation. Their land gave the highest yield of 45 bushels per acre..[9]

By 1980, the numbers had increased. Vandervelde reported that about 19,000 families were resident in the project area, mostly second or third generation sons and daughters of original colonist families for whom no provision for agricultural land was made in the original settlement. (VanderVelde 1982)

The settlements were segregated by ethnic group. Sinhalese settlements were separate from the settlements of the east coast Tamils and Muslims. Nine settlements were located in the Batticaloa District. There were no Sinhalese in these settlements.

From 1950 to 1958, about 43 village units were created in the Left Bank. The Left Bank channel’ extended into Batticaloa District. Sinhalese households were in the majority in the Left Bank. Most of these were settled in the head and middle areas in the Left Bank, while Tamil and Muslim households were located downstream. [10]

The Sinhalese were settled on the favored upper reaches of the Left Bank, immediately below the dam, and the others were allotted less well irrigated lands at the ends of the irrigation channels close to their original settlements, reported Tambiah.

Vandervelde (1982) said that on the Left Bank at the top end all families are Sinhala. They have no problems with irrigation. The middle zone is mixed, majority Muslim with Sinhala and Tamil. They have serious problems with irrigation during the Yala season. At the bottom area families are from the Tamil speaking Muslim community and Tamil community. This area experiences the most acute and persistent water problems, including domestic water, especially during the Yala season.

Wimalaratne & Uphoff (1997) said that the most productive farming in Gal Oya was done in parts of the Right Bank and in the central portion of the system served directly by the Gal Oya River, because these areas had better water supply. The population in these areas was mostly Tamil and Muslim.

The colonists came into Gal Oya at staggered intervals as the main irrigation channels, distribution channels and field channels were developed and the paddy field sites were cleared and leveled. The first batch arrived in Gal Oya in November 1951. [11]

K.A. Podi Menike had come as an eight-year-old with her parents from Gonagala in Kegalle. When her father left his ancestral home and hearth and arrived with only his family and bundles of clothing to make a life here Colony hathalihak hadala minissu dura gam walin genawa, she recalled.

63-year-old Digamadulle said his father was from Hindagala, Peradeniya and his mother from Dunkewila, Gampola. News filtered to Gampola that Gal Oya needed settlers. Seventy-two applications went from their village and nine families, eight of whom were closely related, were chosen after medical check-ups. In 1952 a lorry picked them up and dropped them at the Gampola Railway Station. When they de-trained at Batticaloa, they were met by a Colonization Officer and two Village Officers.

Herath Mudiyanselage Gunaratne came from Badulla. His father grew oranges there for a living but decided to take a chance in the new world of Gal Oya. They were amongst the first settlers, arriving to a literal desert, with all vegetation cleared by huge machinery and set ablaze in the village of Wawinna. Ithama dushkarai api enakota, yana-ena paraval thibbe ne, guru paraval witharai thibbe.” Malaria was rampant and the ambulance was regularly taking the sick to hospital.

Gunaratne attended the new village school which had on its register about 140 children and was the first to pass the Senior School Certificate from there, after which he trained as a teacher and returned to serve the area, retiring as a Principal.

Each colonist family was given a small cottage with three rooms, all tools such as mammoties, pannittu (buckets), kethi (sickles) lanterns, 400 rupees to buy buffaloes for ploughing and two busal of bittara wee (seed paddy) of the Illankaliya variety.

Their new houses were of cement-block walls and tile-roof while a school in the area before the scheme sported only goma-meti biththi (mud walls) and an iluk-thatched roof. The colonists were issued balapatra (permits) for the land they cultivated which were later changed to Swarnabhoomi or Jayabhoomi deeds. .[12]

The original allotments to each peasant family was 4 acres of irrigated paddy land and 3 acres of highland. This was reduced to 3 acres of paddy land and 2 acres of highland in 1953, and still later to 2 acres of paddy land and 1 acre of highland. [13] The families had to have knowledge of farming, [14] be in need of land and their eldest should be a son. [15]

Farmer Organizations were set up. the ‘main channels’ under the Gal Oya Scheme would be looked after by the Irrigation Department, the ‘distribution channels’ jointly by the department and the farmers and the ‘field channels’ by the farmers, using these Farmers Organizationa..[16] ( continued)

[1] https://thuppahis.com/2022/05/20/the-galoya-valley-scheme-the-people-who-made-it-a-reality/ KK de Silva.

[2] https://www.sundaytimes.lk/180204/plus/an-ocean-of-gratefulness-still-flows-279447.html

[3] https://www.iwmi.org/Publications/IWMI_Research_Reports/PDF/PUB018/REPORT18.PDF

[4] https://thuppahis.com/2017/01/14/gal-oya-addressing-errors-in-ajit-kanagasundrams-recollections/ GH Peiris

[5] https://www.lankaweb.com/news/items/2016/10/10/the-gal-oya-project-60-years-on/

[6] Neville ladduwahetty cites Hoole etc. See Island continuation of the 20.5.16 essay

[7]Gamini Iriyagolle The Eastern Province, Tamil Claims and “Colonisation” https://fosus2.tripod.com/fs20000614.htm

[8] https://thuppahis.com/2017/02/02/the-anti-tamil-gal-oya-riots-of-1956/ SJ Tambiah

[9] https://thuppahis.com/2022/05/20/the-galoya-valley-scheme-the-people-who-made-it-a-reality/ KK de Silva.

[10] https://thuppahis.com/2017/01/14/gal-oya-addressing-errors-in-ajit-kanagasundrams-recollections/ GH Peiris

[11] https://thuppahis.com/2017/01/14/gal-oya-addressing-errors-in-ajit-kanagasundrams-recollections/ GH Peiris

[12] https://www.sundaytimes.lk/180204/plus/an-ocean-of-gratefulness-still-flows-279447.html

[13] Economic Review, March, 1977

[14] https://thuppahis.com/2017/02/02/the-anti-tamil-gal-oya-riots-of-1956/ SJ Tambiah

[15] https://www.sundaytimes.lk/180204/plus/an-ocean-of-gratefulness-still-flows-279447.html

[16] https://www.sundaytimes.lk/180204/plus/an-ocean-of-gratefulness-still-flows-279447.html