“SETTLER COLONIALISM” AND TAMIL EELAM Part 2B

Posted on October 22nd, 2024

KAMALIKA PIERIS

In the 20th century too, the British rulers continued to colonize the island with Tamils from India. At a Durbar with Tamil chieftains of Jaffna peninsula in 1911 British Governor Henry McCallum told them that he had reserved the Tank Country and the East for the people of Jaffna. He would bring immigrants from South India, if the Tamils in Jaffna did not comply.[1]

Ponnambalam Ramanathan told the Governor at this same meeting in 1911 that Jaffna people had colonized the land up to Anuradhapura and wanted the government to open up the railways so that more Tamils could come south.[2]

Denham observed in 1911 that Jaffnese do not emigrate as cultivators and settlers but for jobs as educated persons. They are not interested in working to open up the country where they have to work for at least two years before they got a return. [3]

Hennayake looked at the position of the Sinhalese in Vavuniya, Mannar, Anuradhapura and Trincomalee in 1921. In Vavuniya, in 1921 of the four DRO divisions, Vavuniya south had a clear Sinhala majority but this is the smallest of the four divisions, [4] said Hennayake.

In Mannar, in 1921, there was not a single Village Headman/Grama sevaka area where the Sinhala were in a majority. Manner was mainly Tamils and Muslims, and in the southern part of the district, the concentration of Muslims was very high. Only three VH areas in Mannar district had a Sinhala population even above 10%. They were Talaimannar, Pesalai and Musali division. This pattern continued for the next 50 years. The VH/GS areas of the northern part of Mannar was overwhelmingly Tamil, with some Muslim concentrations, said Hennayake.

Anuradhapura district was largely Sinhala in 1921. All the AGA divisions of Anuradhapura have reported a Sinhala majority since the census started in 1871, he said. The Tamil population in Anuradhapura was very low, but they were there. Anuradhapura town has always had a relatively large Tamil population. They were largely engaged in business and related activities, observed Hennayake .The rest of the Tamils were concentrated in Anuradhapura district, Kekirawa and a few rural areas, concluded Hennayake.

Tamil settlers eventually dominated the whole of the Northern Province. Kilinochchi town was colonized in 1936 by residents from Jaffna in order to reduce overpopulation and unemployment in Jaffna.

Tamils and Muslims also became dominant in the Eastern Province in the 20 century. Tamil colonization was only 8 to 16 miles into the interior, on the east coast and the west, said P.A.T. Gunasinghe. [5] That is because the British administration was only interested in access to the Bay of Bengal. They were not interested in the interior of the Eastern Province.

the position in the Eastern Province until Independence, was neglect and decay of the extensive but sparsely populated Sinhala areas and development of the coastal areas (other than the Sinhala Panama Pattu) populated by Tamils and Muslims, said Gamini Iriyagolle .[6] Therefore the population migrated in large numbers to the coastal areas.

The high point for Tamil dominance in Trincomalee was 1920. In 1920, Tamil population In Trincomalee was at a high level and the Sinhala population was at a low level, noted Hennayake. The Tamil separatists argue that the 1920 position should be taken as the ideal and there should be no deviation from this, he observed in 2009.

While Tamil population prospered in the Eastern Province, it was quite the reverse for the Sinhalese, said GH Peiris. Caught by their traditional occupation rice cultivation and reluctant to move from their traditional Purana villages, the Eastern province Sinhalese of the late 19th century and early 20th century, simply wilted, said GH Peiris. The government records of the period show the retreat of these ‘purana’ villages, the depopulation through famines, epidemics, drought and finally, cultural assimilation by other ethnic groups.[7]

Tamil and Muslim populations are thriving, Sinhala villages are dying, said S. O Kanagaratnam, in 1921 in his Monograph on the Batticaloa District.” One of the saddest features is the decay of the Sinhalese population in the west and south of the Batticaloa District. At one time there were flourishing and populous Sinhalese villages, as evidenced by the ruins and remains dotted about this part of the country. Now most of the Sinhalese villages that are left are little better than names. The Batticaloa District had very old stone inscriptions, such as the Nuweragala inscription dated 4 BC found in Bintenne, he observed.[8].

Isolated attempts were made to rescue the Sinhala villages in Batticaloa. In 1922 the British created new Sinhala division In Batticaloa area, Wewgampattu North, taking away the Sinhala villages from Tamil and Muslim domination and placing them under a Kandyan Sinhalese divisional administrator, said Gamini Iriyagolle.

The British authorities continued to favour the Tamils in Trincomalee. The diary of the AGA, Trincomalee for July –August 1933 recorded that the migrant Sinhala fishermen who had come into Trincomalee had clashed with the Tamil fishermen regarding use of the beach.

The British GA had given a decision against the Sinhala fishermen. The Sinhala fishermen had appealed to the Fisheries Department in Colombo. AGA mentioned the continuous succession of interviews; the longest was with a Mr. Subramanian ‘who is still advocating the cause of the Tamil fishermen”, the AGA said, while the AGA was making the entry in his diary.

The population of Tamils in Trincomalee started declining from the 1920s. it was 52.2% in 1921, 46.6% in 1931[9] It went down further in the 1940s when Trincomalee harbor was used by the British South East Asia command, in 1942, during World War II.

The Second World War brought many migrants from all parts of the island to the naval establishment and the Dock Yard at Trincomalee. They also arrived in Trincomalee town. This brought many non-Tamils into Trincomalee, said Peiris and led to a rapid increase of the population. Trincomalee became a major commercial centre as well added DGB de Silva[10]

The food shortage during World War II led to the opening of land in the Trincomalee district for cultivation under the emergency food drive. Land development was carried out in a number of projects in Malaria infested jungles employing southern youth many of whom died of fever. Padaviya and Allai schemes were born as a result of this enterprise. The land Department then functioned under the respected Tamil Civil Servant, Sri Kantha, said DGB de Silva.

The 1946 Census showed that the total Tamil population in 1946 was less than in 1921. In all Tamil districts including Jaffna the Tamils had lost ground between 1921 and 1946. In 1946, Tamils were in a minority, In the Eastern Province except for Trincomalee and Batticaloa Urban Councils where they were in the majority. But Tamil population had increased in all Sinhala districts except for Chilaw, particularly in Badulla, Matale and Nuwara eliya.[11] Michael Roberts noted that in 1946, 22% Tamils resided outside North- East. [12]

Gamini Iriyagolle pointed out that there was no land hunger in Trincomalee, Jaffna, Mannar and Vavuniya districts in 1946. There were few Tamil applicants for the later Allai and Kantalai, colonization schemes of the 1950, he said. [13] Mannar and Vavuniya did not have landlessness in 1951 and Jaffna was adequately served by the Iranamadu colony, observed BH Farmer.[14]

RMAB Dassanayake nostalgically recalls life in Trincomalee in the period 1940-1950 when he used to visit his home in Trincomalee while studying at Kandy. Dassanayake had a special connection with Trincomalee. His grandfather had been Rate Mahatmaya there. Grandfather’s proficiency in the Tamil language was the envy of some of the Tamil officers in the Trincomalee kachcheri. [15]

Dassanayake’s father was at that time Korale Mahatmaya. Father had grown up in Trincomalee .He had studied at Rama Krishna Mission Hindu College at Trincomalee as a resident student and was fluent in spoken and written Tamil. Father conducted his official correspondence in English and Tamil. Dassanayake and father would have received a certain amount of deference and recognition due to grandfather’s status as well as father’s own. That may explain the son’s nostalgic recall.

My father was a connoisseur of the Tamil cuisine, said Dassanayake. During school holidays I remember accompanying my father on a couple of occasions when he visited Trincomalee town where he drew his salary at the kachcheri or attended to other official duties. On one such visit my father took me to a simple Tamil eating house patronized usually by visiting villagers to Trincomalee town. We were served with rice and a variety of fish curry – fried (poriyal) white (vellai) and hot and spicy – (kulambu). We relished those tasty preparations, recalled Dassanayake.

Dassanayake said he can recollect vividly the very peaceful and harmonious co-existence that prevailed between the Sinhala and Tamil communities in his time in those village areas. They interacted like members of closely knit family units. Those who lived in that region then would endorse this statement.

However, Dassanayake’s recall shows the ethnic divisions of the time. ,Kattukulam-Pattu comprised of two sub-divisions, namely Kattukulam-Pattu East and K. P. West, said Dassanayake. The eastern sector comprised mainly of Tamil villages with a sprinkling of two or three Muslim villages, extending from Nilaveli to Pulmoddai along the North eastern coastal belt, .

The western sector-consisted mostly of Sinhala villages with one Muslim and three Tamil villages extending from Morawewa/Pankulam along with Trinco-Anuradhapura road area up to Rotawewa. Branching off on a by-road cross connecting Tiriyaya are the villages of Gomarankadawala, Tavuluwewa, Madawachchiya, Kivulekada and about ten other village units – some of which were then mere hamlets consisting of forty to fifty households in each. The Sinhala sector was supervised by the – Korale Mahatmaya who had five village headmen under him to assist in his duties.

Dassanayake shows the gradual Tamilisation of the administration in Trincomalee district. He said, after my grandfather’s demise the Rate Mahatmayas, then known as Vanniyar Mudaliyars were all Tamil. They were replaced by DROs who were also Tami.. Dassanayake recalls two of them, T. Balasanthiran and V. R. Navaratnarajah

Present day Sri Lankans have swallowed the false statement that the Tamils are the original inhabitants of the Eastern Province. A reader wrote to the “Island’ newspaper, saying that he can find Tamils and Muslims who can trace their ancestry to the North and Eastern province, but that he cannot find any Sinhalese who can do so.

Emil Van der Poorten (b.1939) said I have spent all my holidays since I was a child in Kuchchaveli area, where a maternal uncle was living. His Sinhala wife was to my recollection the only Sinhala speaker for miles around. As an adult I was familiar with the east coast between Verugal and Batticaloa, Panchchankerni area in particular. There were very few Sinhalese there either. [16]

Trincomalee town had Sinhala mudalalis he recalled. The larger towns in Batticaloa also had Sinhala merchants from the south. Apart from them and the migrant fishermen in the wadiyas, there were no other Sinhalese, he said. ‘It is a gross misrepresentation of fact to rewrite history and settle Sinhalese in what was originally Tamil and Muslim country. There was never a significant concentration of Sinhala speakers in those parts of the country,’ he concluded.

Tamil presence in Trincomalee continued to reduce after 1950. In the 1981 Census, there were only 33.8% Tamils in Trincomalee district. Critics pointed out that in 1981 there was only one AGA division, namely Town and Gravets’ division, which is predominantly Tamil.[17]

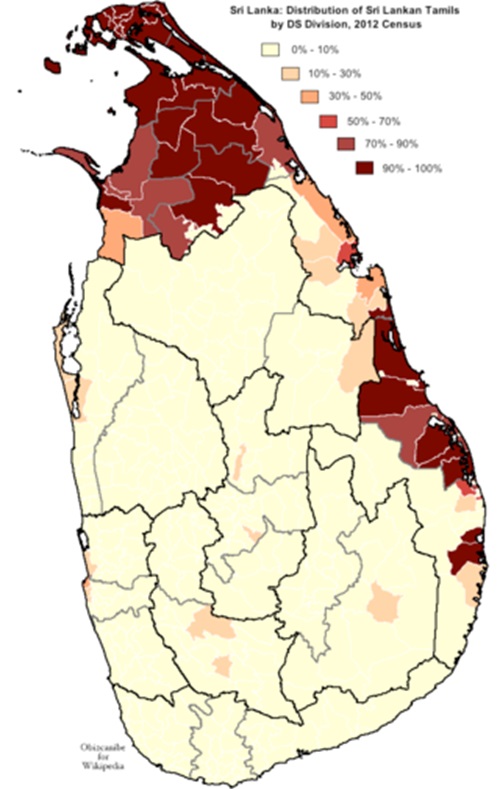

Census of Sri Lanka 2012 showed Trincomalee district having 26.7% Sinhala 31.1 % Tamil and 41.8% Muslim. Wikipedia map showing Distribution of Sri Lankan Tamil people in Sri Lanka by DS Division according 2012 Census” is given below. (Continued)

[1] Bandu de Silva. Tobacco gold that made Jaffna assertive. Island sat mag. 1.4.2006 p 1. Records of the Durbar with Tamil chieftain 1911(SLNA)

[2] Bandu de Silva. Tobacco gold that madke Jaffna assertive. Island sat mag. 1.4.2006 p 1. Records of the Durbar with Tamil chieftain 1911(SLNA)

[3] Denham, Census of 1911 p 69

[4] Shantha Hennayake. Island 2.5.2009 p 10

[5] P.A.T Gunasinghe ‘Tamils of Sri Lanka’ p 44

[6]Gamini Iriyagolle The Eastern Province, Tamil Claims and “Colonisation”https://fosus2.tripod.com/fs20000614.htm

[7] GH Peiris p 19

[8] S.O. Canagaretnam “Monograph on the Batticaloa District of the Eastern Province of Ceylon” p vi

[9] GH Pieris p 25, 29.

[10] DGB de Silva Island Sat Mag 11.6.2005

[11] Census 1946 Vol 1 Pt 1 p 156, 157

[12] M Roberts confrontation in Sri Lanka . p 232

[13] Iriyagolle p 1.’Island’ 18.6.95 , P 7.

[14] Farmer p 218

[15]R. M. A. B. Dassanayake Memories of better days — pre-1960 era in Trincomalee districthttps://www.infolanka.com/org/srilanka/hist/84.htm

[16] Sunday Leader.1.3.2009 p 15

[17] Cecil Dharmasena. ‘Irrigation and settlements schemes in Northern and East’ Daily News 26.10.95 p 23.